M

iguel* squats down in front of the prison entrance with two other inmates. He has just arrived with only a blue backpack carrying his possessions. Gates at opposite ends of a narrow staircase spell the difference between freedom and imprisonment for him.

Now this is his life, crammed with other inmates inside the country's most overcrowded jail.

At least he may be safer here than outside. JO2 Lucila Abarca of Quezon City Jail says some inmates incarcerated for drug crimes are afraid of getting out as it might mean death for them.

Rich or poor, I do not give a sh*t. My order to the police not only to kill, whatever. Destroy.

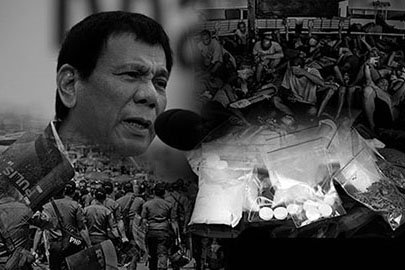

Beyond the prison walls President Rodrigo Duterte's drug war has claimed over 3,000 lives since the tough-talking former Davao City mayor took office over two months ago. More than 1,000 were killed in police operations for allegedly resisting arrest, while a greater number were "deaths under investigation" — believed to be carried out by vigilantes.

Duterte has promised a bloody war against drugs during his campaign and he has been consistent in fulfilling it. He says many more will be killed to rid the country of illegal drugs, a menace which hurts all sectors of society.

"Rich or poor, I do not give a sh*t," he says. "My order to the police not only to kill, whatever. Destroy."

The government plans to suppress drugs in three to six months through its "Double Barrel" campaign.

The Philippines' top cop Director General Ronald dela Rosa explains that in one strike, the barrel will fire two triggers: One aimed at high-value targets; the other at street-level personalities.

Critics, however, claim the president's war is anti-poor and disregards human rights.

Poverty and drug use: A vicious cycle

Miguel* will join the 2,349 other inmates at the Quezon City Jail who committed drug crimes. They form 60.87 percent of the overall population at the prison, which can ideally accommodate only 800. Inside the facility, it is hot and crowded that inmates sweat just by standing still.

He says he got imprisoned after police came to his house for "Oplan Tokhang" or "Knock and Plead," an operation where cops go house-to-house and ask suspected drug users and pushers to voluntarily surrender. When his girlfriend found out that her name is on the watch list, she immediately surrendered but Miguel* did not.

He admits to using shabu for seven years since he was 23 years old — something that relieves his fatigue and gives him the rush of energy he needs in his work as a construction worker. But he denies the non-bailable charge of drug possession against him. He says the evidence was planted.

According to him, police asked him for P200,000, but lacking the money, he opted for jail instead. Still, he worries how his three children will fare without him.

READ: Upholding fundamental rights

Problems of economic exclusion, daily violence, neglect, joblessness and hopelessness that drive illegal drug use are far more intense amid the squalor of urban poor communities than in the exclusive enclaves of the wealthy.

Life is precarious for his family. He earns P1,000-P1,200 for three to four days worth of work as a mason. Of his earnings, he spends P300-P400 for his addiction. "My body desires for it," he says.

Poor people are more vulnerable to drug abuse not because they have discretionary income but because they are more likely to live on the margins of society, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime's (UNODC) 2016 World Drug Report.

"You substitute drugs for something else. You substitute them with feelings of accomplishment, you substitute them with love and reassurance, you substitute drugs for answers that they may have never been able to find," says Dr. Alfonso Villaroman, chief of the Health department's Treatment and Rehabilitation Center in Bicutan.

The UNODC report adds that without realistic hopes of a better future, those belonging to marginalized groups are more vulnerable to illegal drug use. At the same time, drug use can also exacerbate poverty and marginalization, creating a vicious cycle.

Jose Enrique Africa, executive director of think tank IBON Foundation, says "problems of economic exclusion, daily violence, neglect, joblessness and hopelessness that drive illegal drug use are far more intense amid the squalor of urban poor communities than in the exclusive enclaves of the wealthy."

Data released by the Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) in 2015 shows that drug abusers are usually male, unemployed and poor. It says they commonly belong to families with an average monthly income of P10,172, below the 2015 national poverty threshold of P10,969 per month or the money needed by a family of five to afford life's necessities.

A closer look at drugs and crime

Al*, another inmate in Quezon City Jail, has been imprisoned nine times, all of them related to drugs.

"It is great that this time I was not included on the list of those killed. I thank the Lord. I was brought again to Quezon City Jail alive," he says.

Duterte says drug dependents rob or kill because they need the fix. "Now, crime has gone down because everybody is afraid," the president says in a speech in August.

Carta explains there are two reasons why drug offenders return to old habits. First, they may be in broken families. Second, it is because of poverty.

"In drugs, money is quick," she says.

According to the UNODC, criminal involvement such as drug trafficking is viewed as the only feasible strategy for upward mobility in some extremely unequal societies.

It is great that this time I was not included on the list of those killed. I thank the Lord. I was brought again to Quezon City Jail alive.

Methamphetamine hydrochloride or shabu is the most used illegal drug in the country, 2015 data of the DDB show.

"Methamphetamine is a stimulant, unlike the others that put you to sleep — that sedate you, right? That's why it's a favorite among long-haul drivers, those who work long hours at night, it becomes their drug to make them function in society," Dr. Ted Herbosa, former Johns Hopkins School of Public Health's regional coordinator for Asia and chief of the trauma division of the Philippine General Hospital's surgery department, explains.

"Unfortunately, it's also the root of many crimes," he adds.

As a trauma surgeon, Herbosa says a lot of patients they treat are victimized by someone who uses shabu.

"Directly, they take it [and] they become violent. Some, indirectly. They needed money, they wanted to hold someone up, they end up killing them," he says.

Illegal drugs is an issue close to home for those in the slums.

"It's a matter of seeing an addict just stabbing one of their neighbors, beating up their wives. Some of them are accused of recruiting young mothers to become drug mules so it's a really big issue," sociologist Nicole Curato says.

This is why some of the poorest communities also support the drug war.

"They feel like those who wronged them, when they're shot dead, can no longer come back. So in a way it restores some level of safety. It's there. The source of legitimacy is present," Curato adds.

Critics, however, point out that the drug war comes down harder on the poor and not just because there are more poor drug users.

To this, the president answered that more poor people are killed because they are easy targets.

"A greater number, unfortunately though, I am not insulting Filipinos, are the poor because they are the easy target," Duterte says.

High-profile government officials who are allegedly involved in the narcotics trade have been publicly named by Duterte in his shame campaign.

But they can afford to meet with the Philippine National Police (PNP) chief to clear their name unlike the many small-time drug peddlers whose corpses wrapped with duct tape are left on the streets.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein last week called out the president for his statements which "display a striking lack of understanding of our human rights institutions and the principles which keep societies safe."

"Empowering police forces to shoot to kill any individual whom they claim to suspect of drug crimes, with or without evidence, undermines justice," he says.

"The people of the Philippines have a right to judicial institutions that are impartial, and operate under due process guarantees; and they have a right to a police force that serves justice."

A greater number, unfortunately though, I am not insulting Filipinos, are the poor because they are the easy target.

Latest data of the UNODC on drug-related crimes show that in 2008 the Philippines had a rate of 11.3 offenders per 100,000 population, among the lowest in the countries it listed. Philippine population was around 90 million that year.

Meanwhile, drug killings in less than 100 days of the Duterte administration have exceeded the average 1,202 murders a year in the country based on 2010-2015 data of the PNP across the top 15 cities with the highest number of index crime or crimes against persons or property.

READ: Perception game: Examining the drug 'crisis'

Al* says he wants to turn over a new leaf if he gets out. But if he gets killed for the drug crimes he committed, it is okay with him — even if Duterte himself shoots him. He says he supports the president's campaign and even wanted to vote for him last elections.

Winning the war

Over half a million drug users and pushers have surrendered to the police, a sign of the war's success, according to the government. But alleged extrajudicial and vigilante killings of drug suspects earned criticisms locally and internationally, pushing the Senate to conduct an inquiry.

Curato says measuring the success of the drug war depends on whose perspective you are using.

If you base it on the government's policy "and it's very clear [in] saying that violence is very much part of it then yes, we are succeeding," she says. "But the broader question is: Is that the policy that we really want to take?"

"We basically institutionalize violence as a way of rendering justice. That's not sustainable," she adds. "So I guess what I'm saying is I understand where this is coming from as a sociologist but as a citizen I'm very skeptical of this war."

Africa says success measured by the huge number of alleged drug suspects killed by police or unknown vigilantes is a false sign of progress in the war against drugs.

The term "drug war" in itself has been contended globally, as labeling it a "war" makes people feel like they themselves are the targets and not the illegal drugs.

It is possible for the government to also eventually target big fish although this remains to be seen... These generate headline-friendly numbers and statistics on killed or apprehended and drug hauls — but the underlying illegal drug problem remains albeit with an ever-changing cast of characters.

In a letter sent to the UN ahead of the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on the World Drug Problem last April, more than 1,000 world leaders tagged the global war on drugs as "disastrous."

"The drug control regime that emerged during the last century has proven disastrous for global health, security and human rights," the letter read.

"Focused overwhelmingly on criminalization and punishment, it created a vast illicit market that has enriched criminal organizations, corrupted governments, triggered explosive violence, distorted economic markets and undermined basic moral values."

Africa says even if some big-time drug lords are caught, it is possible that the vacuum created in the illegal drug economy will just give rise to other drug lords ready to take their place as shown by experiences in the US, Colombia, Mexico and Thailand where violent crackdowns on drugs were found ineffective.

READ: Trends at our doorstep

"These generate headline-friendly numbers and statistics on killed or apprehended and drug hauls — but the underlying illegal drug problem remains albeit with an ever-changing cast of characters," he says.

The president's hatred for illegal drugs is unquestionable — a stance he has long held since his time as Davao City mayor.

"There will be no let-up in this campaign," Duterte says during his first State of the Nation Address.

The war will stay on course and remain bloody in the next six years.

"We will not stop until the last drug lord, the last financier and the last pusher have surrendered or been put behind bars or are below the ground if they so wish."

* Names withheld to protect identity.

Editor's note: All Filipino quotes are translated to English.