The plunge

"S

abi nila, 'Heto, subukan natin,'" Charles* recalls. "We did it for the sake of trying, until it became a monthly thing." The next thing he knew, it cost him his calmness. What came next was his job.

He hopes his son won't be next.

Charles is a first-timer in Bicutan's rehabilitation and treatment facility. Bill*,on the other hand, considers himself an "experienced patient" after a tragic relapse. They were both methamphetamine users.

But they both came from different worlds.

Charles, a former graphic artist who hustled his way through three firms, hails from a neighborhood he describes as "so busy, the moment you'd wake up from bed you'd emerge from market stalls." Bill, who once worked as a call center supervisor, came from a well-off family—the kind that affords to send their kids to a high school in Italy. The kind that owns multiple houses across Manila.

Both Charles and Bill say they picked up the habit simply because they belonged to a wrong, uneducated bunch. Both are remorseful and optimistic that there's life after rehabilitation.

But more importantly, they consider themselves lucky. If not for little epiphanies, they believe they'd still be stuck in the same rut.

Arman* fancies himself as a "functional" cannabis user. He had been under the influence for eight years now, and never, according to him, has the habit got in the way of his job as a creative. Neither has it spilled over family affairs and friendship.

He looks back at the first day he tried smoking pot which he says he was triggered by genuine curiosity. Prior to weed, his poison of choice was alcohol. But he had long kicked the habit of heavy drinking after learning that the weed made him less grumpy. That it enabled him to sleep easily. Most of all, it made him happy.

All I know is that he was a dependent, who could have had a fighting chance in life had he gotten the help he needed.

Emma Cruz lives in a family where most of the men used drugs, but at the same time, she couldn't say that she had a difficult childhood.

"One of my uncles, whose life had been entirely eaten away by drugs, was the most hands-on parent I've got when mom was overseas and dad was busy at work. He made sure I ate on time, I took a bath on time, and I got to school on time. He did it every day, tirelessly. His everyday life revolved around mine. And that's because he has barely lived his," she recalls.

"I didn't know the entire story of his addiction. All I know is that he was a dependent, who could have had a fighting chance in life had he gotten the help he needed. He was never violent, compared to my other uncle who never used drugs but always threw violent fits whenever he was drunk. At one point, he even aimed a gun at my cousin and his wife," she adds.

Judith's* son has tried it all. At 39, his addiction has spanned a decade. Whenever he's strapped on cash, he'd pass on the regular meth and grass in exchange for something more accessible: solvent.

"It's hard fending off rumors," Judith says. "Neighbors say my son's a thief, a criminal. They say I'm a neglectful mother."

As much as she wants to help out her son, Judith is left with nothing but hope. Her son, she says, could barely make ends meet and feed his two kids as a construction worker; what more having to pay for treatment?

"How can I send my son to rehab when I can't even eat thrice a day?" she says.

Bill and Charles are optimistic on having a new life. The former, after his time in Bicutan Treatment and Rehabilitation Center (TRC), is set to move in the province with his wife and son. The latter, on the other hand, bares he hasn't figured it out yet. He just thinks he only has to avoid the places where he has earned a notorious reputation as a user and peddler.

Arman, for his part, thinks he doesn't need help. As he would put it, he's chill.

But the same could not be said for Cruz.

"Instead of having hope for my tito, I now fear for his life," she says.

And that goes for Judith's son, too.

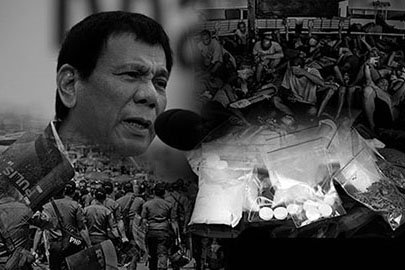

When President Rodrigo Duterte assumed office, among the first items he wanted to tick off his to-do list was the country's drug problem. He was harsh and unapologetic about it. And he approached it so ruthlessly, it earned the ire of various sectors of Philippine society and abroad.

It was only after 57 days that the new administration openly acknowledged the drug problem as a public health concern. During the same period, health and human rights have taken center-stage in a polarized and divisive debate. The body count from the "War on Drugs" has been on a steady rise, hogging both the national and international spotlight.

Last August, the president made a remark regarding drug peddlers and users that put the administration's approach on the drug menace in the most harshest of lights: "Are they humans?"

Confronted with figures from Western countries, swayed by the trends slowly being adopted by Asian neighbors, a critical question has cropped up: Are we wasting lives rather than saving them?

* Names were withheld upon request.

Patients before criminals

Philippine General Hospital's Dr. Ted Herbosa, who was once Johns Hopkins School of Public Health's regional coordinator for Asia and undersecretary at the Department of Health, believes it's high time that the State looked at this menace through a new lens.

Trends at our doorstep

The bitter reality of lives destroyed by drug abuse requires us to look for effective solutions to the problem.

While some countries opted to take harsh, iron-fist tactics, imposing severe punishments for drug offenders, others have started to emphasize more comprehensive, community-based approaches to tackling drugs, treating it as a public health issue rather than a crime.

Mexico, for example, has been embroiled in a bloody drug war ever since former president Felipe Calderon launched an all-out campaign against the feuding cartels in December 2006.

Mexico's "kingpin strategy," which focuses on taking down the drug lords and leaders of the drug cartels, nearly tripled its homicide rate under Calderon and had done little to quell violence and bring security to the country.

Portugal, on the other hand, took a radically different approach. Rather than focusing on law enforcement, the government of Portugal decided to decriminalize the possession of all drugs, from marijuana to heroin. Combined with a focus on prevention, education and harm-reduction, Portuguese officials worked on reintegrating drug addicts back into the community rather than isolate them in prisons.

Authorities there neither arrest drug users found with small amounts or with less than a ten-day supply of an illegal drug (i.e. a gram of marijuana). They are instead made to appear before the so-called "dissuasion panels," composed of a lawyer, doctor and psychologist, who only has three choices: prescribe treatment (voluntarily), impose fine, or enforce no sanction at all. Drug dealers and traffickers, on the other hand, were sent to prison.

In 2012, members of the ASEAN huddled and envisioned themselves to be 'drug free' by 2015.

Last April, the Drug Policy Alliance wrote the United Nations an open letter calling for systemic reforms in the world's approach on the drug epidemic. This was signed by over 1,000 world leaders on the eve of the UN General Assembly Special Session on the World Drug Problem.

Gloria Lai, senior policy officer for the International Drug Policy Consortium, notes that most Asian countries now have harm reduction programs, although they are not enough to meet the needs.

Last year, nine Asian countries met with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to agree to transition toward voluntary, community-based services for drug users instead of the traditional approach of employing harsh punishments for drug offenders such as executions, forced and arbitrary detentions, beatings, whipping and even hard labor.

Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand and the Philippines indicated that roughly 50 to 70 percent of their prisoners in jail for drug-related crimes. Indonesia is currently preparing executions for drug trafficking.

In 2012, member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations huddled and envisioned themselves to be "drug free" by 2015. But a year after the deadline, illegal drugs continue to plague the region.

Meanwhile, a leading global health commission in Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health called for new policies to transform existing approach to drug use, addiction and control worldwide, and putting a premium on policies that reduce violence and discrimination in drug policing, access to controlled medicines and social services for users.

Narcotics 101

Dealing with a problem calls for a systematic approach. And an essential part of that is knowing the basics. Here are the basics on the Philippines' narcotics problem.

They say "Knowing is half the battle." Here are the basics on the Philippines' narcotics problem.

Your Brain on Drugs

Some say it fries your brain. Others note that it hinders cognitive function. Many claim it makes you see things. But what really happens to someone who takes the plunge? And just how thin is the line for someone before he stumbles on a steep slope? Two experts walk us through.

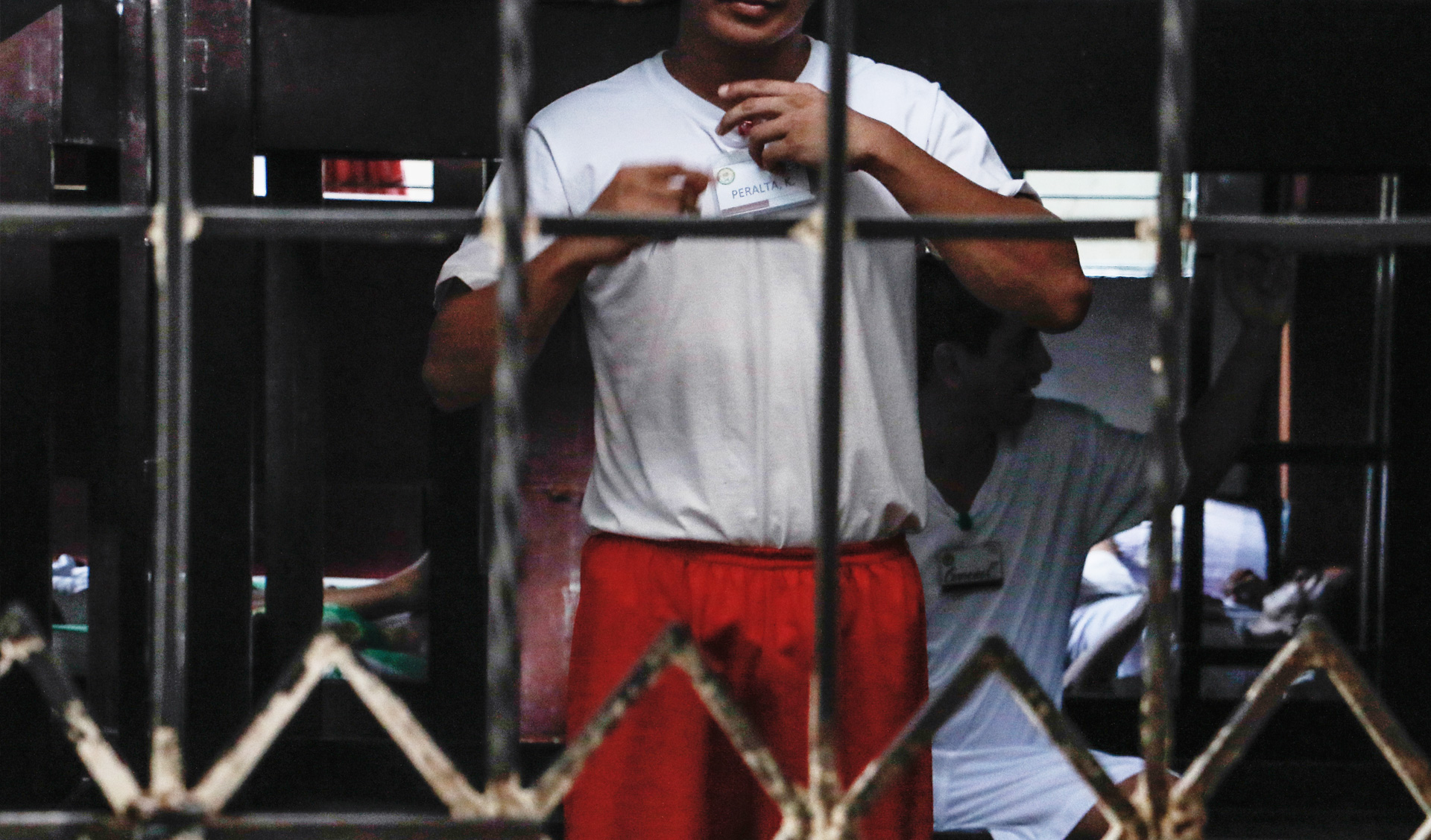

Inside a rehabilitation facility

With the government waging a relentless crackdown on both peddlers and users, the elephant in the room needed to be addressed.

"What to do with the people who turn themselves in?"

Philstar's NewsLab team went to the country's biggest rehabilitation and treatment center located in Bicutan, Taguig, in an effort to verify if there's any truth to such correlation.

'Overpopulated,' not 'crammed'

The spike in "surrenderees" (coined by the government) has been affirmed by both Dr. Herbosa and Bicutan TRC chief Dr. Alfonso Villaroman. This has been echoed by other health experts and local government units (LGUs) in fear that treatment centers might soon struggle with admissions.

"The number suddenly increased this month, a spike attributed to the series of surrenders of drug personalities following an intensified anti-drug campaign of the Duterte administration," said physician Gene Gulanes, manager of the Davao City Treatment and Rehabilitation Center for Drug Dependents.

As of December 2015, the Department of Health has accredited 15 government-owned and 27 private treatment and rehabilitation centers, according to a DDB report.

These centers use a wide range of scientific and therapeutic approaches, which include involving other family members into the rehabilitation process.

However, admissions in treatment and rehabilitation centers have slightly increased in the previous years.

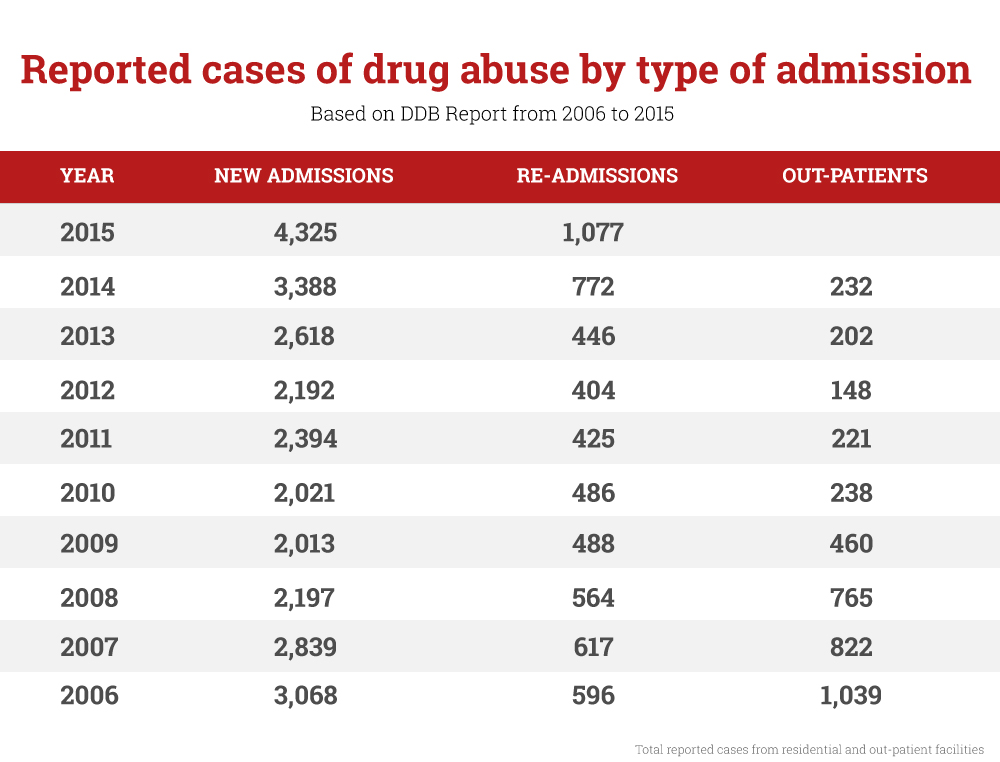

In 2015, a total of 5,402 admissions were reported, 4,325 of which were new admissions and 1,077 were relapsed or re-admitted cases from either the same or different facilities.

This represents an increase of 29.86 percent from the previous year, which is attributed to several factors such as an intensified advocacy program and increased law enforcement operations.

Should the center continue to be flooded with court orders for more admissions of clients, "I would probably be forced to write back the court and respectfully decline," Gulanes adds.

Aside from drug users' families' financial limitations and denial about their loved ones' drug-dependence, there is still a social stigma that comes with drug addiction.

"Because there's also a social stigma that comes with drug addiction and sometimes they would be stigmatized to the point that after they are rehabilitated, they are criticized for once being a drug dependent or drug abuser," says Dr. Jerome Go, a psychiatrist at the Chinese General Hospital and the University of the East Ramon Magsaysay Memorial Medical Center.

This social stigma, according to Go, dissuades people from seeking treatment.

The psychiatrist says that when drug users are rehabilitated, it should be more than just detoxifying them or cleaning their bodies from drugs.

"(It) is also changing their mindset and instilling hope to patients that change is possible," says Go.

Dr. Villaroman disputed a claim that the Bicutan TRC—the biggest and second oldest in the country—was crammed. While it is true that the DOH's Facilities and Services Regulatory Bureau accredited the complex for 500 patients, it is better than other alternatives. "If we turn them away, where do we put them?"

The facility's current estimates tally 1,600 patients.

Based on the data of the Philippine National Police, there are 710,961 drug surrenderees as of September 13.

Modes of rehab treatment

Getting into a rehab

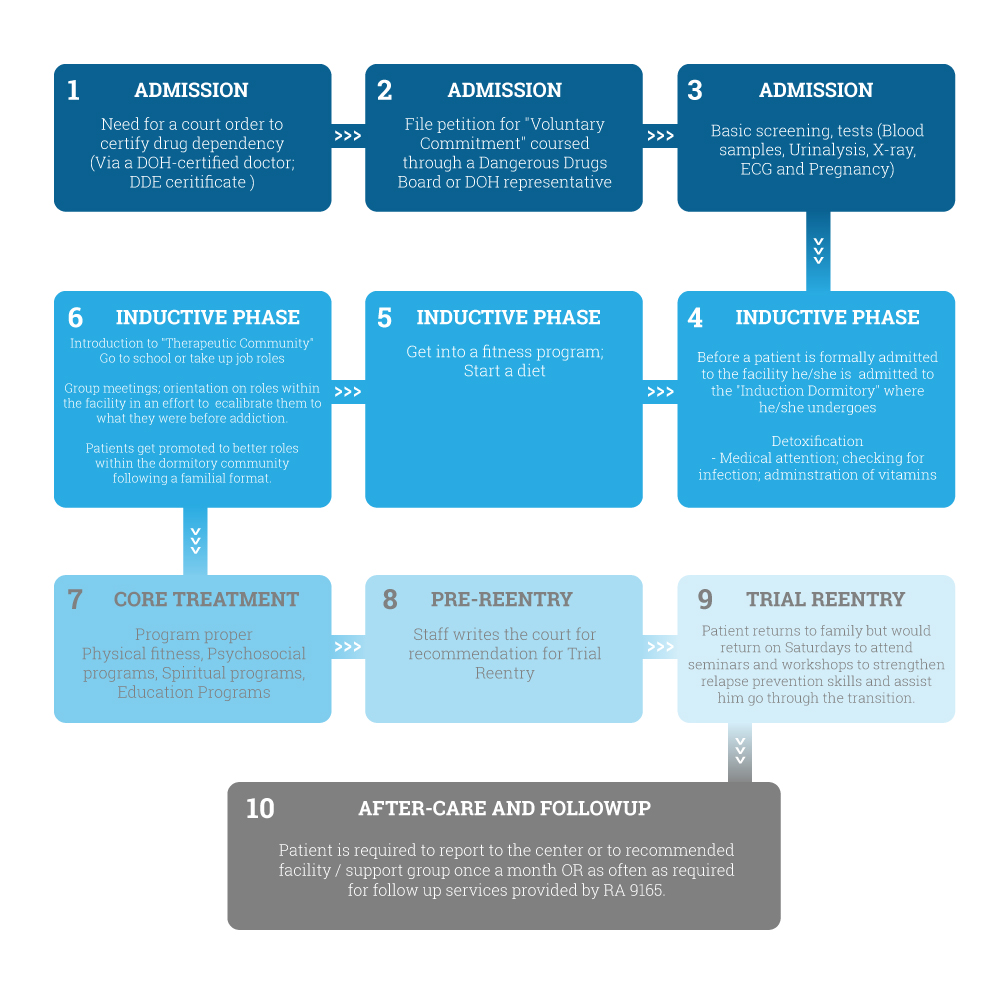

Contrary to popular belief, going to rehab is not like going through a psych ward, with tubes and all.

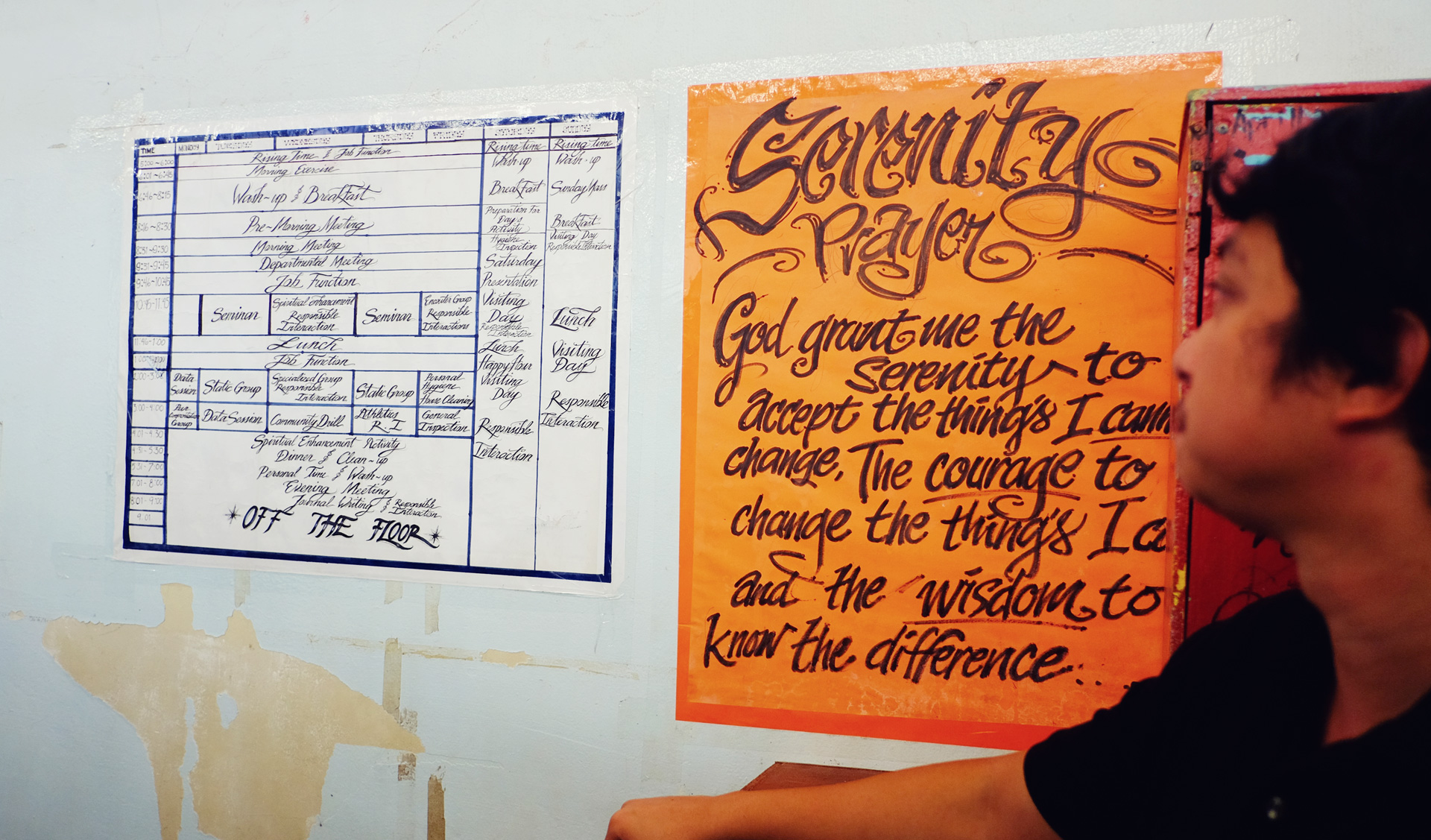

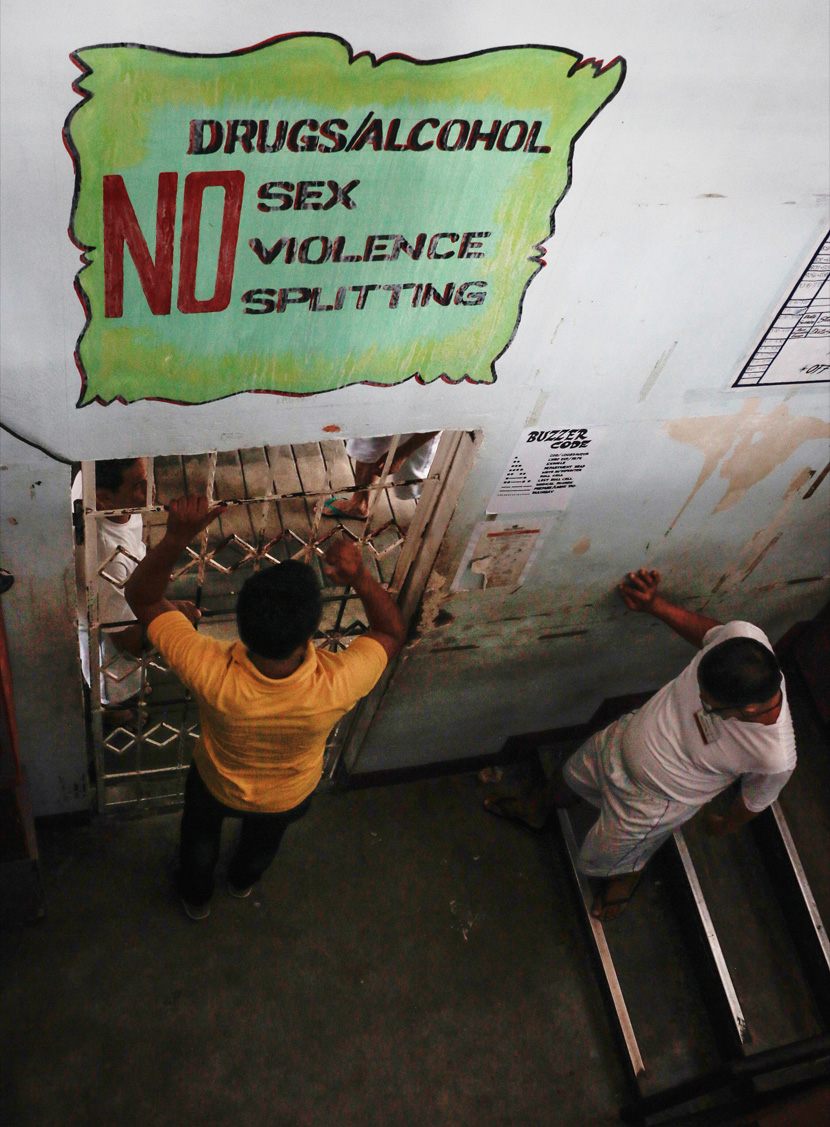

TRCs, on hindsight, should be likened to hospitals, and not prison camps. After all, people go to these facilities to seek help. Their common denominator: Treatment.

Drug dependents who wish to enter rehab can enjoy different modes of treatment in rehabilitation centers.

The Multidisciplinary Team approach employs the services of different professionals. A team composed of a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, occupational therapist and professionals from other related disciplines cooperate with the drug dependent and his family.

The Therapeutic Community approach—which the Bicutan TRC employs—is a highly structured program wherein the community is utilized as the primary vehicle to foster change. Patients are thrust to the community, and role modeling is a significant part of the program.

The Hazelden-Minnesotta Model views addiction as a disease and that a patient does not have control with the external factors. The Spiritual approach uses the Bible and views drug addiction as a sin. The Eclectic Approach combines all of the approach for a holistic rehabilitation program.

Why bother saving them?

Dr. Villamoran notes that seeking help via rehab is also seeking help from within. And according to Dr. Herbosa, drug dependents should not hesitate. After all, it is founded on an ancient creed from which all doctors subscribe to.

'Health continuum' and the state's premium

The idea of sending addicts to rehabilitation is usually met with disdain—especially for tax-payers who deem drug users as free-loaders.

"Why would we pay for their treatment?"

Having been in the frontlines himself for five years, Dr. Herbosa walks us through a possible approach and an essential question: "Where to put the money?"

Are we even asking the right questions?

Is it a wart on the Philippine society? Is it brought by poverty? Is this a by-product of poor enforcement of the law?

Sometimes, complex problems require going back to the drawing board. Dr. Herbosa posits revisiting the questions that have shaped our approach on this pesky problem.