O

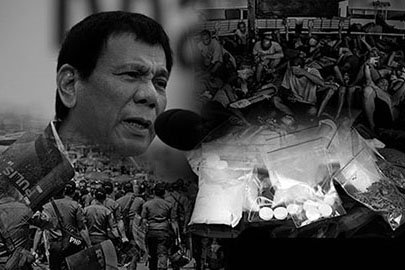

n June 30, Rodrigo Duterte, long-time mayor of Davao City, became president of the Republic of the Philippines and promised a relentless and sustained fight against crime, drugs and corruption.

"My adherence to due process and the rule of law is uncompromising," he promised in his inaugural speech.

His administration has pointed at a 31-percent drop in the number of index crimes -- 11,800 in July this year against 17,105 in July 2015 -- as proof of that the rule of law is being observed.

According to Philippine National Police Director General Ronald dela Rosa, the number of rapes – an index crime-- has gone down by 49 percent.

But the rule of law is more than just crime volume, according to the World Justice Project, which has been compiling a Rule of Law Index since 2012, where the Philippines advanced to the 51st slot out of 102 countries in 2015 from 60th in 2014.

Rule of law also includes accountability under the law for the government, its officials and agents as well as for individuals and private companies. Laws must also be clear, publicized, stable, just and must be applied evenly.

Even in the 2015 index, where the Philippines was ninth of 15 countries in East Asia and the Pacific, the country scored the highest in Order and Security, with a score of 0.71 against a perfect score of 1.

Its lowest score -- a high of 0.50 in 2014 -- was in Absence of Corruption, which looks into "bribery, improper influence by public or private interests and misappropriation of public funds or other resources."

The Office of the Ombudsman has been probing and prosecuting cases of corruption against officials, particularly those implicated in the so-called Pork Barrel Scam, which it continues to investigate.

By June, it had already filed 418 cases against 357 filed in 2015, Malaya reported in August. Since 2011, when Conchita Carpio Morales was appointed ombudsman, her office has already filed 3,519 cases at the Sandiganbayan anti-graft court.

Upholding fundamental rights

Upholding the rule of law also includes protecting individual rights "including the security of persons and property and certain core human rights."

According to the WJP report in 2015, "a system of positive law that fails to respect core human rights established under international law is at best 'rule by law', and does not deserve to be called a rule of law system."

Here, the Philippines scored 0.52 in the 2014 and 2015 indexes, down from 0.60 in 2012-2013.

This has been a prickly issue for the Duterte administration, with the president reacting to concerns raised by the United Nations and the US to a spate of drug-related killings in recent months as interference in domestic affairs.

Officially, security forces involved in the government's war on drugs are only authorized to shoot back in self-defense, a point that both Duterte and PNP chief dela Rosa have stressed.

Both have also made off-the-cuff remarks, however, that human rights advocates have said tend to encourage the extrajudicial killings of drug suspects.

Duterte has, in the past, said that he will kill drug lords and drug dealers and has told citizens that they can try to arrest drug dealers and kill them if they are armed and they resist

"Directives of this nature are irresponsible in the extreme and amount to incitement to violence and killing, a crime under international law. It is effectively a license to kill," UN special rapporteur Agnes Callamard said in August.

"As long as Duterte is a cheerleader for the summary killing of criminal suspects, the fundamental right to life of all Filipinos is at risk from state-sanctioned murder," Human Rights Watch, one of the groups to first express alarm over the deaths, said in a dispatch in July.

It must be noted, however, that even in 2012, the WJP said upholding fundamental rights in the Philippines was problematic "particularly in regard to violations against the right to life and security of the person, police abuses, due process violations and harsh conditions at correctional facilities."

Human Rights Watch also criticized the Aquino administration in 2012 for what it saw as a failure to address extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances.

Justice delayed

The WJP also says "the process by which the laws are enacted, administered, and enforced [must be] accessible, fair and efficient" and justice must be timely and delivered by competent, ethical and independent representatives "of sufficient number, have adequate resources, and reflect the makeup of the communities they serve."

This is where the Philippines scored worst -- 0.38 in 2015 against 0.36 in 2014 -- with particularly poor scores in the timeliness (0.32) and impartiality (0.28) of the criminal justice system. It also scored 0.18 in the effectiveness of the correctional system in reducing criminal behavior.

Duterte, a former prosecutor, has himself expressed frustration at the slow pace of the Philippine justice system from getting warrants issued to resolving cases.

"What is the fastest decision you made on criminal cases?" he said in a speech in August in response to a comment to Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno's advice to judges allegedly involved in the drug trade not to surrender unless a warrant of arrest had been issued against them.

In a meeting with the media in August, Sereno said the judiciary is already working on clearing its backlog of cases through "decongestion officers" and the use of "e-courts", where court activity can be consolidated and tracked electronically.

For the past five years, the National Prosecution Service has filed 126,016 drug-related cases in court, only 3,482 -- 2.76 percent -- of which have led to a conviction.

"For [a] majority of them, Information (a formal charge) has been filed in court," Senior State Prosecutor Richard Fadullon, speaking at a Senate hearing this month, said of the remainder.

Justice Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre II, at the same hearing, said that the Office of the President has received 3,081 cases for review since July 2010. He added 1,581 had been subjected to automatic review, of which, 1,469 were resolved.

The prosecutor general, meanwhile, has 22 pending motions for reconsideration and has resolved nine motions for reconsideration on automatic-review cases. New to the post, the Justice secretary said he was not aware "whether the cases were dismissed favorably or against."

Former Justice Secretary Leila De Lima, now a senator, attributed the low conviction rate to the lower threshold for evidence for filing cases.

"Kapag probable cause lang ho kasi sometimes may tendency kasi na after preliminary investigation stage, tatamarin na ang mga imbestigador, tatamarin na 'yung mga prosecutor na kumuha pa ng more evidence, na mag-case buildup pa para ma-achieve yung proof beyond reasonable doubt," De Lima said at the hearing.

Aside from the low conviction rate, the swamped criminal justice system has led to long trial times. Fadullon said drug cases take an average of eight years to resolve.

"So, sa dami ho nung kaso na iyan, ito hong mga taong ito, most are under preventive detention. Karamihan dito ay nililitis pa hanggang sa ngayon," Fadullon said, adding around just 10 percent of drug cases involve "big-time" dealers.

It does not help that law enforcers and prosecutors sometimes don't seem to be working together, as Sen. Vicente Sotto III – former chairman of the Dangerous Drugs Board, which sets the country's drug policy – pointed out at the hearing.

"'Pag sinita mo mga prosecutor e, sasabihin, 'Sir 'yung mga PDEA (Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency) niyo, tsaka mga pulis niyo 'di marunong mag-file ng kaso, 'di marunong magprepare ng kaso.' Kapag sinita mo PDEA, 'pag sinita mo pulis, 'anong nangyari?'... Ang sagot sakin, 'Hindi sir, 'yung mga prosecutor niyo nalalagyan. Nakita niyo 'yung miscoordination?" Sotto said.

Sotto and De Lima's concerns echo a 2009 VERA Files report that cited "interagency conflicts" as well as bribery as among the flaws of prosecution that led to low conviction rates.

It recalled the case of Chinese national Cai Qing Hai, who was on the list of Asia's most wanted drug manufacturers and traffickers and whose case was dismissed due to lack of probable cause.

Government lawyers also prematurely judged police operations as irregular due to alleged bribery, VERA Files reported. The case also showed that the fight against illegal drugs is weakened by unappreciated evidence.

The chief justice, meanwhile, has said that the delays and dismissals of many drug cases are attributable to the failure of police witnesses to attend trial and a lack of prosecutors and public attorneys. Evidence can also be weakened by poor observance of the chain of custody and proper inventory of seized drugs.

Increase in cases as drug war continues

The war on drugs, launched almost as soon as Duterte became president has led to an increase in cases, the Public Attorney's Office, which provides legal services to indigent litigants, told Philstar.com in an e-mail.

According to PAO lawyer John Philip Reyes, the number of criminal cases the office is handling has increased by 43.85 percent since June 30, with drug-related cases increasing 41.22 percent.

For comparison, the PAO handled 698,886 criminal cases in 2015 -- 85,133 of those related to drugs – and resolved 35.14 percent of those.

All this despite a lack of funds for the continuous training of PAO lawyers and a lack of approved public attorney positions, which the PAO said should be equal to the number of courts in the country. It plans to address this by hiring more lawyers and staff.

It also has insufficient space at the central and district offices, a problem it hopes to solve by asking the Budget department for money for its own building. The Department of Justice has already proposed a budget of P2.6 billion for the PAO in the 2017 budget.

Reyes said that despite the limitations, "skillfully facilitated the release and favorable disposition of cases of indigent clients involved in drugs cases" by assigning a full-time public attorney at each of the country's drug courts.

The Supreme Court, in July, designated 240 additional trial courts nationwide to handle cases involving violations of the Dangerous Drugs Act.

SC spokesperson Theodore Te said the high tribunal decided to add more courts because, with 128,368 cases already being heard in drug courts, the number of courts "will be insufficient considering the steady rise of new drug-related cases.

Partly due to the heavy caseloads and the limited resources, PAO supports Olan Tokhang, where police visit drug suspects in their homes to ask them to surrender and promise to stay away from drugs, because "instead of filing charges against them and putting them in prison, chances were given to them to rectify their wrongdoings."

PAO hopes that the campaign would "significantly lessen cases filed in court and instead opportunities be given to them to improve their lives."

But the 600,000 that have surrendered in Tokhang operations across the country do not necessarily indicate success, John Collins, chief of the London School of Economics' Drug Policy Initiative, says.

"This is like saying a violent war on poverty has been 'successful' because thousands of poor people had 'surrendered'. Now what? There is no treatment infrastructure in place," he says.

Drug personalities as victims: 'Tokhang' in a Rizal barangay

by AJ Bolando

A barangay in Rizal province sees drug users and pushers as victims and wants to help them turn over a new leaf

Amid the rising number of deaths in linked to the government's drive against illegal drugs, a barangay in Rizal is exerting all of its means to avoid bloodshed.

A first-class urban area of Barangay Sto. Domingo in Cainta, Rizal is very keen on the campaign to resolve the sale and use of drugs in their area. The local government, however, considers those on their drug watch list victims due to various reasons, including poverty.

Barangay Chairperson Janice Tacsagon and Barangay Councilor Reynaldo Vila have been offering seminars and activities for alleged drug users and peddlers who have surrendered in the government's "Oplan Tokhang"

As of Sept 5, Barangay Sto. Domingo has conducted Tokhang in a third of its area, which has an estimated 54,000 residents. It has yielded them 149 "surrenderers" from a verified watch list of around 500 persons.

The barangay coordinates with Philippine National Police, Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency and Department of Social Welfare and Development to persuade drug users and peddlers, whether on their list or not, to turn themselves over.

The barangay councilor, who heads the peace and order committee, is confident that the individuals on their list are drug users and peddlers since the list has gone through a thorough validation and investigation.

The list came from different sources, including information from their own assets, and statements from neighbors of suspected drug personalities.

"Aside from the assets, we are conducting our own investigation in the surroundings of the identified drug personality," Vila explained.

The list is forwarded to local police, who will also verify the information and cross check the names against their own list. However, in other places, the list given to police was unverified, leading to non-users being included.

"Before we submit it to the PNP talagang dumaraan sa evaluation and investigation just to assure na walang taong ilalagay sa watchlist na hindi naman involved sa drugs," he added. Vila said that most on the list denied their involvement at first.

Vila said that while they risk their lives for every knock on a door, they are still lucky that all drug personalities have agreed to coordinate with them.

He shared that they serve as front liners during Tokhang, while law enforcement is just there for security.

"Yan ang iniiwasan namin, na matakot iyong taong involved sa drugs. Kapag nakita nila na may mga pulis agad. Kasi kung may baril sila (police), ilag na 'yang mga 'yan," the councilor explained.

Barangay Sto. Domingo is serious in helping the victims of illegal drugs. In fact, it is allotting five percent of its budget for Tokhang and for rehabilitation.

Aside from processing the rehabilitation of the "surrenderers" at Camp Bagong Diwa in Taguig, they also have a moral recovery program, a livelihood program and community services "to help them avoid engaging in illegal drugs."

The barangay has also launched an assistance desk for drug "surrenderers".

"We are more on encouragement para matulungan sila dahil we believe that drug users and pushers are also victims," Vila said.

The drug personalities who turned themselves in are required to give an affidavit, personal files and other information that would help the authorities crack down other drug personalities.

After the process, "surrenderers" are allowed to go home and live normal lives.Vila said that they are still monitoring the drug "surrenderers" to ensure that they do not go back to illegal drugs.

"Kailangan pa rin naman nila maging visible sa aming barangay, pero kung babalik sila (illegal drug activities) nasa sa kanila 'yun," Vila said. He said that if the "surrenderers" do that, they will be charged.

If proven that the "surrenderers" still use or sell drugs, a buy-bust operation or raid will follow.In one of his speech for the 115th anniversary of the PNP, Director General Ronald "Bato" Dela Rosa said that the role of the barangay officials in a drug-free country is important.

"Napakalaki ng aming tungkulin dahil kung barangay ang pag-uusapan we are the frontliners kapag dating sa peace and order, kami ay hindi rin tumitigil sa pagsasagawa ng community relations, " Vila said.

While the residents of Sto. Domingo are fortunate to have decent officials, other barangays in the country are not. Some officials are in the drug trade and serve as protectors and Vila claimed that he knows some of them.

"Ayoko na lang magsalita tungkol sa kanila kasi siguro magkakaiba kami kasi ng pananaw at sistema ng panunungkulan."

*The Department of the Interior and Local Government prefers the term "surrenderers" to surrenderees.

The drug watch lists used as bases for Oplan Tokhang have also been questioned, with anecdotes of non-users being included in the lists popping up on social media. Some "surrenderers" have also ended up dead in later police operations because they returned to using or selling drugs.

Others have been killed by unknown gunmen, their deaths attributed to drug syndicates and other criminals.

A similar list, of government officials allegedly involved in drugs, was met with denials and trips to police headquarters to clear things up. Others on the list were unable to issue denials, being dead.

As of this post, no formal charges have been filed against those named on the second list.

The government has said, however, that making the list public has given those named a chance to clear their names. This, despite the presumption of innocence afforded by the law.

In the case of the judges named in the "narco-list", the chief justice, in a letter to Duterte said they "may have been rendered vulnerable and veritable targets for any of those persons and groups who may consider judges as acceptable collateral damage in the 'war on drugs.'"

They are not the only ones in danger, Fr. Shay Cullen of the PREDA Foundation, which promotes human rights, especially those of abused children, notes in a commentary on Union of Catholic Asian News (UCAN).

"No warrant or proof of guilt or innocence is needed. All those named as suspects are judged guilty by being on the list of suspects," he wrote after two children -- five-year-old Danica Mae Garcia of Dagupan City and four-year-old Althea Fhem Barbon of Guihulngan, Negros Oriental -- were killed by bullets meant for relatives on the drug watch list.

"It is a policy that has put the power of hearsay and the dubious list of suspects in the place of hard evidence. It has bypassed the rule of law and entered the realm of lawlessness. The gun has replaced the courtroom and the balance of right and wrong," he said.