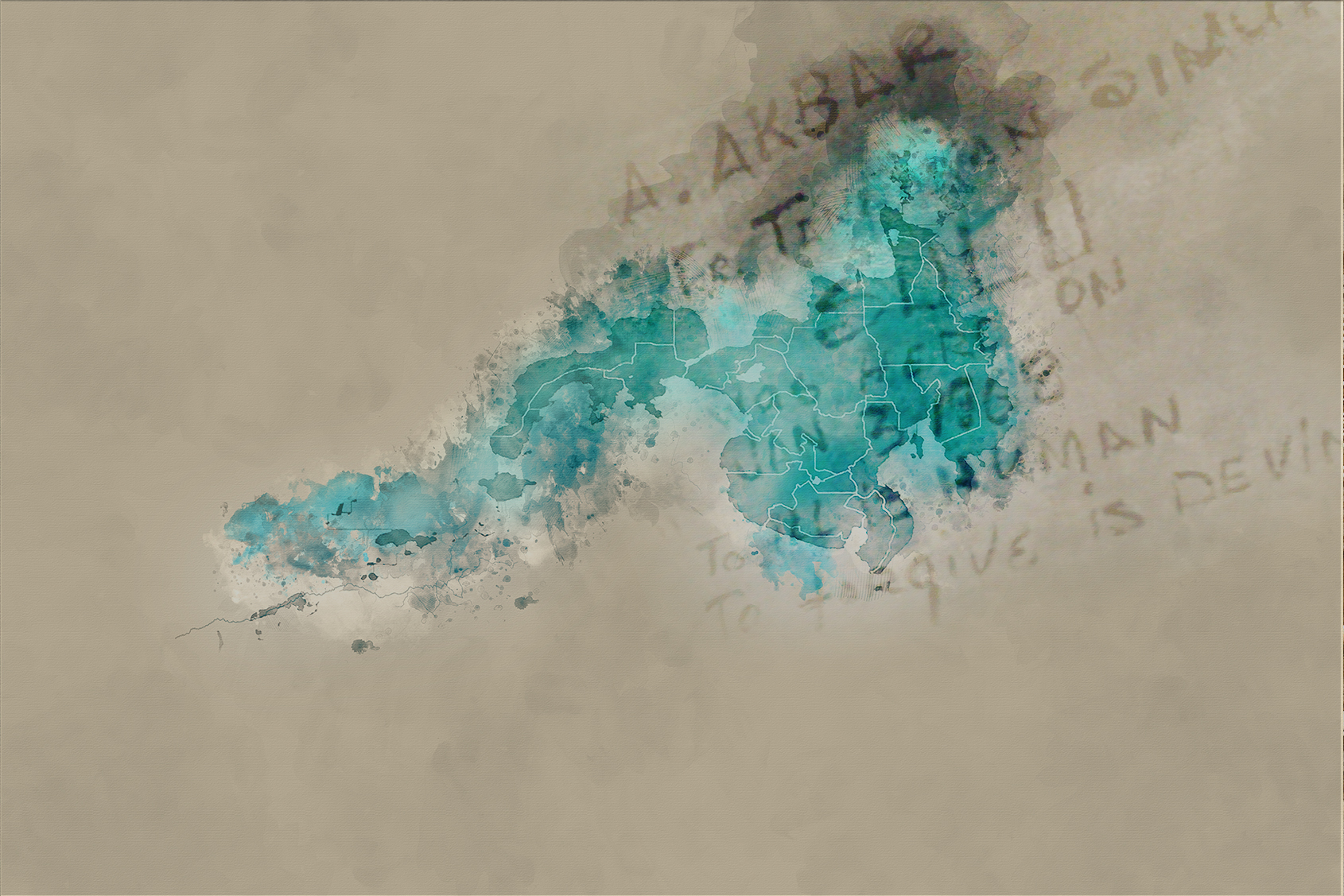

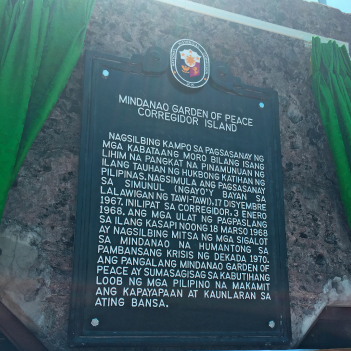

In a part of Corregidor Island in Manila Bay is the Mindanao Garden of Peace, a memorial to the "Jabidah" massacre, an atrocity that some argue did not happen at all.

A marker in the garden identifies the island as a site where a contingent of Moro youth was trained by elements of the Armed Forces the Philippines in 1968.

What happened in March—the supposed deaths of at least 28 recruits—has been described as a historical injustice by Moro advocacy groups and as a hoax by, for example, Marcos loyalist and failed KBL senatorial candidate Larry Gadon.

"In our minds and hearts, there is no question that it happened and that it is true. In our history, there is no question about its rightful place in the long narrative of our struggle for self-determination," Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao Regional Gov. Mujiv Hataman said in a commemoration of Jabidah in 2016.

He said the killings, which have been dismissed by some as part of a political ploy to discredit the Marcos administration, left "a mark akin to a wound that has never fully healed as its scab is picked over and over again with every other act of injustice committed against our people."

What is beyond debate, however, is that the massacre led to fighting in Mindanao that was used partially to justify the declaration of martial law in 1972 and had already taken at least 120,000 lives 20 years later.

"The so-called Jabidah massacre had a galvanizing effect on the Muslim student community in Manila," Thomas McKenna wrote in "Muslim Rulers and Rebels: Everyday Politics and Armed Separatism in the Southern Philippines"—the primary source for an Official Gazette timeline article on the massacre.

"Throughout the year, Muslim students protested against the Jabidah killings. The Jabidah protests transformed one campus activist in particular into a Muslim separatist," McKenna wrote of Nur Misuari, a Tausug scholar and activist who would become the founding chairman of the Moro Nationalist Liberation Front.

President Rodrigo Duterte, who considers Misuari a friend, has himself said that the conflict in Mindanao is rooted in Moro nationalism. Less acknowledged is how those roots were watered by blood spilled while the father of Duterte's political ally, former Sen. Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr., was president.

Less acknowledged is how the roots of the Mindanao conflict were watered by blood spilled while Ferdinand Marcos was president.

In an editorial issued months before the remains of ousted dictator Ferdinand Marcos were hastily interred at the Libingan ng mga Bayani in Taguig, the MILF, expressed the rebel group's objection to it.

"In fact, the Moros suffered the most numbers of killed or victims during the height of Martial Law, in particular those victims of massacres. This is not to include the thousands upon thousands of hectares of Moro and other indigenous peoples' ancestral lands in Mindanao given to migrants or outsiders," the Luwaran.net editorial said.

But Jabidah was just one of the events that contributed to the rise of the Muslim separatist movement in Mindanao, writes Temario Rivera in "The Moro Reader: History and Contemporary Struggles of the Bangsamoro People." In response to the massacre, Datu Udtog Matalam, governor of Cotabato province, founded the Muslim Independence Movement.

That movement gained traction after mass killings of Muslims between 1971 and 1972 in central Mindanao that were perpetrated by paramilitary groups and "provoked by escalating ethnic, economic and political tensions between Christian and Muslim communities."

Among those groups was the Ilaga militia group, which has been implicated in at least 20 massacres and atrocities in Mindanao.

Malisbong and Tictapul

Beyond books and dry historical accounts, Laisa Masuhud Alamia, a human rights lawyer and executive secretary of the ARMM government, narrated her childhood in Tictapul in Zamboanga City.

"It was my first playground, with a river running through it. I remember looking out our window and saw coconut trees that seemed to go all the way up the sky. It was magical! I remember my brothers on a small boat rowing down the river, happily jumping into its depths. We lived a simple life then," she said in a personal Facebook post that Philstar.com was allowed to quote.

"More than 400 men, women and children were massacred there in 1977," she said.

"Martial law reminds me of my mother. They looted her house, store and bodega of copra, rice and sugar, before they burned everything down. Some of our relatives and workers survived. Others weren't so lucky. Among those dead was a Christian cousin of mine. Muslims, Christians, even the carabaos and cows, were not spared, survivors said."

Alamia and her mother were spared because they were away when the killings happened, but the incident nevertheless left a mark.

"Martial law reminds me of the light that was in my mother's eyes, the smile on her lips, her natural joie de vivre— all gone. She didn't really die in 2002 when she finally left us. She died on the day she learned of the massacre in Tictapul back in 1977.

"No, don't talk to me about how it was better during the time of Marcos. Don't talk to me about apologies and non-apologies. Don't talk to me about forgetting these and moving on. Indeed, some of us survived martial law and rebuilt our lives after the massacres in Tictapul and other areas in the country. But to this day, justice has not been served. No amount of compensation or apology would make up for what was lost. — Laisa Masuhud Alamia

Amir Mawalil of the Young Moro Professionals Network and new Office on Bangsamoro Youth Affairs chief wrote in September 2016 about the military "pacification" operations in 1974 in Malisbong, in what is now Sultan Kudarat.

"'Pacification' during the Martial Law years meant that the men of the village were to be forcibly sent to the village mosque, while women and children were dragged for interrogation to warships docked nearby... Pacification then for the people of Malisbong was a euphemism for mass murder," Mawalil said of the incident where 1,500 people died.

On Sept. 24, 1974, close to 300 houses were burned in Malisbong, and boys as young as 11 were rounded up and sent to the Tacbil mosque with men as old as 70. They were shot at point-blank range.

Women, "girls and grandmothers alike," were raped, Mawalil wrote.

"The rape of women and mass murder of men, and the destruction of property in Malisbong were, without question, sponsored by the state. It was an act of violence against the people of Malisbong under the auspices of then President Ferdinand Marcos," he said.

"Our elders passed on their account of history to us so we can learn from it, and our history is replete with stories of how Martial Law has changed the lives of our people," the YMPN said in a statement after the Marcos burial. "To deny that these atrocities happened and to forget the suffering it has caused is to betray our history as people who fought for freedom from the dark days of dictatorship."

To deny that these atrocities happened and to forget the suffering it has caused is to betray our history as people who fought for freedom from the dark days of dictatorship.

While the government in Manila has decided that this year's celebration of the 1986 People Power Revolution, which toppled Marcos from power, will focus on "moving forward" instead of being "stuck in the past," that will be a more difficult for the Bangsamoro to do.

Guiamel Alim, chairman of the Consortium of Bangsamoro Civil Society and who works with the Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission, said the Moros have yet to move on from the massacres and displacements in the 1970s.

"No reparation, no justice, no institutional reform and structural changes. Simply said, the Bangsamoro has not recovered from these war atrocities," he said.

"They still remember how their relatives were massacred, their women raped and the ultimate result of social dis-integration. No justice served to the victims of Martial law. Only when transitional justice will make the Bangsamoro feel lighthearted after what happened in the 1970s," he also said in an email to Philstar.com.

Among those overtures for transitional justice was the dedication of the Mindanao Garden of Peace in 2015, but a bigger step is the anticipated passage of the Bangsamoro Basic Law and the creation of a new political entity that will have more autonomy than the ARMM and that will remain a part of the Republic of the Philippines.

"Marcos' legacy to the Bangsamoro was the deteriorating peace and order situation that the Moro are still experiencing until now," the CBCS said in a separate email.

That includes poverty in Moro areas and ancestral land lost to land-grabbing.

"Now, the Moro have became alien in their own land, denied the justice for all the wrongs brought to them," it also said.

"Lastly," the CBCS said, "martial law planted hatred in the hearts of the Bangsamoro and the idea that guns, rather than the state, are what's needed for protection." — Philstar.com NewsLab