Many of the fictions concocted by the Marcos family have left an indelible mark in today's political discourse.

And one of the most enduring? It's neither the nuclear plants nor the forged war records.

It's a piece of bread that for sure, many of today's adults have heard: The Nutribun.

For many millennials, the word "Nutribun" wouldn't ring a bell. But for the generations who lived through the Marcoses' might, it's easily a throwback to a life's phase.

"It's nothing like the pan de sal we all eat now," Alvin Toledano narrated in Filipino. "It was bigger than a coaster. It was something that was given to us in school for 'merienda.'"

"It's as big as a burger bun," he adds. "Although it's bigger, much more dense, and tastier than the modern counterpart."

Toledano belonged to a generation where they could barely ask what the Nutribun was. Yes, he could remember how it looked like. Yes, he could recall how it was a part of the daily school grind. Yes, he's able to reminisce how it tasted.

But to remember why he had it in the first place? No.

Toledano was born in 1975—right smack in the Martial Law period. Whenever he looks back at the time when he ate the Nutribun, all he could remember was school.

Many of the Marcos myths bounce between the spectrums of fraudulent and absurd. But the Nutribun story has been the most divisive.

The most ardent of the strongman's supporters assert that it was one of the Marcos presidency's best contributions to Philippine society.

Daily bread

Wading through Facebook with the texts "Nutribun" and "Marcos" leads to myriad pages reinforcing the Marcos supporters' claims.

On many occasions, these pages use the Nutribun anecdote as a springboard to refute the plunder and abuses that the Marcos administration had committed.

"[B]inusog mo ang mga kabataan noon, at may disiplina sila noong panahon mo," one Facebook page's entry read.

"Noon may libreng gatas na Klim, tinapay na Nutribun at Trigo or Bulgur na pinamimigay araw-araw sa mga public schools para malabanan ang malnutrisyon sa bansa natin," another stated.

"Pero nung sa nawala si Marcos at si Cory Aquino na ang presidente unti-unting nawala ang libreng [Nutribun]," it added.

But for staunch critics, it's just another well-oiled cog in the credit-grabbing machine that the Marcoses employ to date.

Credit grabbing

Recent reportage points us to the bread being a product of the United States Agency for International Development's (USAID) mission in the country during the late 1960s.

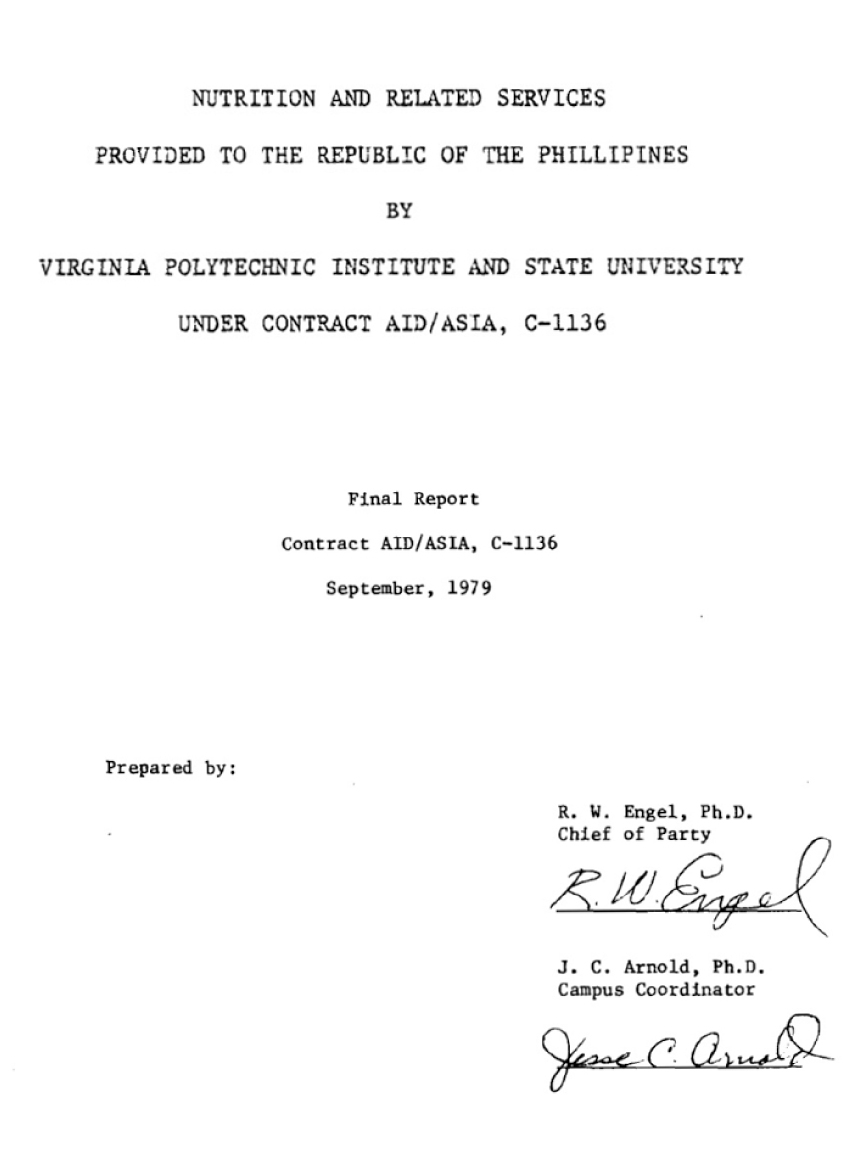

A document was made available online by the same US humanitarian body. The same trove of documents detail the development of a "convenience food" to "supplement in elementary school feeding programs."

Further examination on the 1979 document indicated that, "USAID Nutrition was responsible for development of the formula to justify a claim for nutritious snack food ... [It] made its decision to combine its Food for Peace and its nutrition activities and to target its food donations to the malnourished child population."

"Through operational research support to Catholic Relief Services and Foster Parents, the AID nutrition office had developed a methodology for a 'Targetted Maternal Child Health Program; and had begun testing the 'nutribun,' a ready-to-eat bakery-bun snack food for school children," it furthered.

MAIN INGREDIENTS

FLOUR, WATER, YEAST, SALT, SUGAR, OIL

FOOD ENERGY

(per 80 grams(2.8 oz) serving)

400 kcal(1675 kj)

The 383-page report, which was furnished by none other than the mission's chief of party Dr. Reuben William Engel, bared essential details on the snack food—its ingredients, how many students were involved in the initial serving, its evolution into "Nutribun," and eventually, how it became the stuff of many Philippine households.

USAID Nutrition was responsible for development of the formula to justify a claim for nutritious snack food.

"I know in my heart it was tasty. The teachers gave it to us during afternoons," Toledano recalls. "But what I didn't know at that time that it was part of the government's projects. Eventually, I would learn of it as part of the Marcos administration's many projects."

Was it?

Careful examination of the paper would tell that a food snack's development came in 1970. This coincides with the establishment of "Project Tulungan," which was spearheaded by the then First Lady herself, Imelda Marcos. The private entity paved the way for a collaboration between the Nutrition and Population offices of USAID in Manila using the "Targeted Maternal Child Health Program."

"The project represented a first major effort to combine nutrition and basic health services with family planning services, initially in Manila and other city slums and later extended to rural areas," Engel's record said.

It was in the "Great Flood" of 1972 when the bread gained household buzz. In a 1974 edition of the journal International Nutrition, Dr. Grace Goldsmith wrote that "8 million nutribuns were airdropped to about one million people in the most severely affected area. The bakeries shifted from schools to disaster feeding."

But it was also during this period when the Marcos administration pulled off a treacherous act, according to American Nancy Dammann, a longtime media advisor for the USAID.

In her memoir published in 2003, Dammann wrote, "the nutribun bags were being stamped with the slogan 'Courtesy of Imelda Marcos — Tulungan project.'"

The Nutribun bags were being stamped with the slogan 'Courtesy of Imelda Marcos.

"The wives of several American officials helped package rice and nutribuns (a horrible bun made with high-vitamin, milk-content flour invented by an AID official and donated by USAID) for distribution to flood victims," she wrote.

"Provincial politicians also stamped food packages with their names," an excerpt of the chapter also read.

The Nutribun, went on to fill the tummies of many Filipino children. The bread continued to be an essential to be a part of various administrations' thrust for proper nutrition. It last saw action in 1997.

In 2014, the Manila government, under the rule then president and now Mayor Joseph Estrada, revived the vitamin-enriched bread. The next year, then Valenzuela solon Sherwin Gatchalian pushed for the bun's relaunch on a national scale.

In 2016, it returned. Sort of. But now, more divisive than ever. — Philstar.com NewsLab