Shortly after academics slammed his "revisionist" view, defeated vice presidential aspirant Bongbong Marcos denied having said that the years of his father, the dictator Ferdinand, were the Philippines' golden age. But on the campaign trail last year, Marcos Jr. did fuel the myth by praising his father's "good work" which for him continues to benefit the people.

The prosperity myth has endured for decades despite a peaceful revolution that drove the autocrat from power. Marcos supporters usually back their view with mini-narratives on the narrow peso-to-dollar conversion rate, growth in early Marcos years, free-flowing traffic, enthusiastic government spending and the country's regional competitiveness, among others.

Experts such as Cesar Polvorosa Jr. of Canada's Humber Business School say, however, that economic performance under any given administration should be measured by the sustainability of growth and its benefits to the general population.

"Other aspects of economic policymaking simply follow from those two major issues. Promoting economic growth enhances employment and livelihood opportunities," Polvorosa wrote last year.

THE EC NOMY

NOMY

UNDER MARCOS

-1960'S-

Marcos assumed

presidency

Campaign period (Overspending, raiding of public treasury)

Export became

sluggish

ISI stagnant

Reelection

of Marcos

Balance of

payments crisis

Devaluation,

fueled inflation

-1970'S-

Martial law

Incoherent

development

strategies

Promotion

of exports

Protection of

ISI firms

External funds for

borrowing remained

available

Debt-driven growth

(foreign loans sustained growth)

Centralized,

longer term control

over state apparatus

-1980'S-

Economic crisis

intensified after

assassination of Aquino

Crony abuses

brought economic

disaster

IMF becomes vengeful

God and limits

Philippines' borrowings

Unpopularity

of the regime

*Based on 'The Philippine Economy: Development, Policies and Challenges' (2003) by Arsenio Balisacan and Hall Hill, Oxford University Press

Retelling the tragedy necessarily starts with a picture of the economy in a dismal state, worse than it had ever been, in the years leading to the ouster of the Marcos family in 1986. It is a story of debt, deprivation and the spoils of a dictatorship.

Debts and downturns

The country was deep in debt—owing $24 billion by 1984 to be exact—with major businesses having absorbed much funding despite lacking in productivity. Massive government construction projects remained either unfinished or without immediate socioeconomic yield. There was a broad gap in incomes of the richest and poorest, while prices of goods skyrocketed. Only a few families controlled and benefited from key industries. The list went on.

Economists from the University of the Philippines led by Emmanuel de Dios sought answers on the crisis felt then. Was it mainly an effect of external shocks, as Marcos supporters claimed? Was it because of the assassination of opposition leader Sen. Ninoy Aquino in 1983? Or was the downturn primarily due to Marcos' policies and abuses?

They found all three factors playing a role, but the explanation that best satisfied their inquiries pointed to a concentration of power in government and its economic policies that dug deeper and deeper holes.

"While the Philippines experienced more or less the same external shocks as other developing countries, there is a residual variation in its performance and response which makes it fall below the average for countries in its class," they wrote.

Needless to say, the economy did not simply sink overnight.

Myth: The region's powerhouse

In the 1950s, the Philippines was second to Japan in terms of per capita income in the region. The country enjoyed moderate economic growth alongside its neighbors while focusing on imports. A common anachronism today's apologists commit is to label this relatively prosperous time part of the "Marcos period."

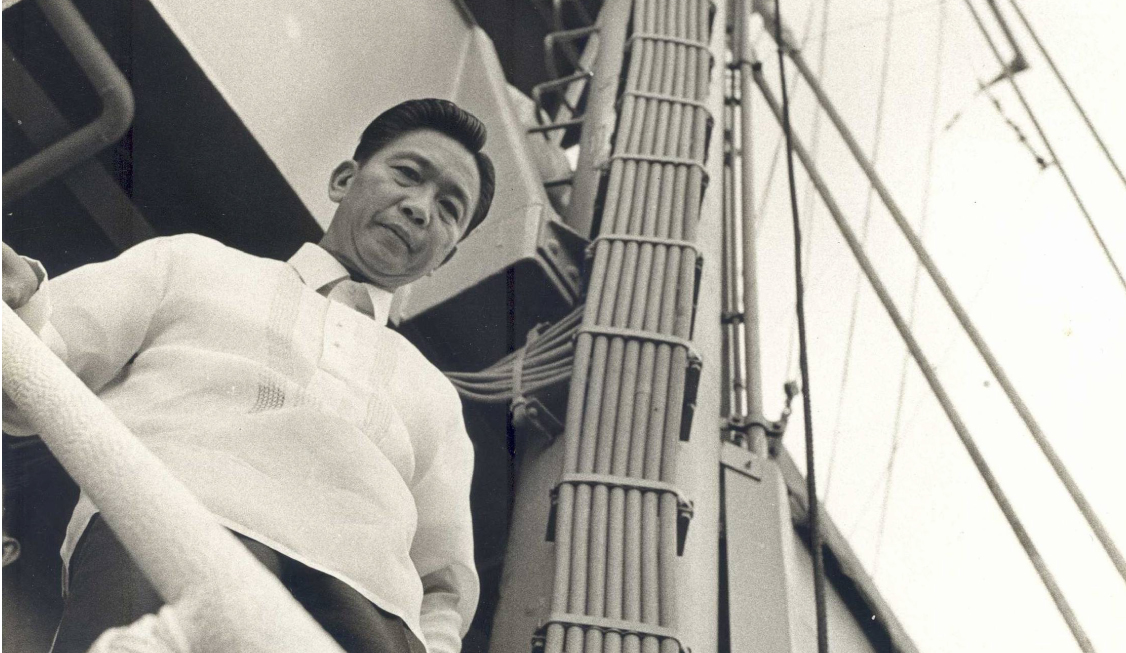

Marcos assumed the presidency only in 1965, when things started to spiral downward in the late 1960s as existing policies no longer encouraged rapid growth. The would-be dictator then pursued an aggressive, expensive run for a second term by foraying into the public treasury to boost his campaign, buy votes and threaten voters. The peso crashed in late 1969, and by the dawn of the following year it lost half its value, Conrado de Quiros wrote in "Dead Aim."

The 1960s crisis, for economists Arsenio Balisacan and Hall Hill, "was triggered by one politician's particularly shameless efforts to maintain a grasp on the reins of the political machinery."

Among its peers, the country could no longer keep up. "While the Philippines started with the highest growth rates for [Southeast Asia] in 1950-1960 (3.6 percent annually), it lagged behind its neighbors in 1960-1970," economists De Dios, Dante Canlas, Solita Monsod and their fellow U.P. economists wrote.

THEN AND NOW:

HOW MARCOS' YEARS COMPARE

Source: * An Analysis of the Philippine Economic Crisis' (1984) edited by Emmanuel de Dios, University of the Philippines; World Development Indicators

To deal with external shocks and a campaign spree that ingested ridiculous amounts in the guise of government projects, the country resorted to debt, and according to the U.S. Library of Congress, was behind by $2.3 billion in payment due in the early 1970s. Then came a pattern of chronic borrowing, devaluation of the peso which bloated prices of goods, and reckless spending.

Myth: A spectacular economy and showmanship

More debts were incurred to pay outstanding debts and to stimulate the economy. The debt-fueled boom in the early 1970s coupled with sweeping reforms and infrastructure programs deceived many, providing the semblance of stability Marcos needed to calm the business elite after he placed the country under martial law.

"The trouble with debt-driven growth with populist tendencies is that it produces a buoyant economic environment—at least in the beginning. As long as the facade of investment for competitiveness is still there, then investors continue to pour money into the economy, which keeps it growing," Harvard-trained economist Ronald Mendoza, dean of the Ateneo School of Government, explained to Philstar.com.

"Initially, it looks very good," Mendoza admitted. "It doesn't take rocket science to figure out that the country's debt-driven growth was a party that would soon end, once investors figured out that despite the mounting debt, the country failed to effectively invest in key infrastructure and competitiveness-enhancing projects."

The 1970s saw the kind of progress without momentum. As then Social Security System chief Adrian Cristobal told Harvard University fellow William Overholt, "It was like an old lady taking off her girdle. Everything just fell out."

The regime's initial reforms turned upside down as institutions bowed to corruption, red tape, inefficiency and Marcos-led cronyism. His development strategies and trade policies were likewise incoherent, not to mention the padding of debt mainly for a gamut of projects that required large funding despite little gain.

Overholt said these included hosting of ostentatious international meetings. International Monetary Fund delegates, for example, were each assigned a brand new Mercedes Benz that was afterward sold as a second-hand car.

The wastefulness could not be exaggerated. Explaining the capital-output ratio at the time, Overholt said it was typical for Asia-Pacific countries to spend $2 to $4 to raise national output by $1. But the Philippines was spending $9 for every buck.

It was typical for Asia-Pacific countries to spend $2 to $4 to raise national ouput by $1. But the Philippines was spending $9 for every dollar.

Debt climbed to $17.2 billion by 1980, and the rate of gross national product—which measures the total value of production—took a dive. Already crippled, the Philippines was gasping for air when world recession hit and its exports suffered way worse than those of its neighbors.

"External factors could help trigger a crisis; but domestic fundamentals (or the lack of it) will dictate resilience to these external shocks. For the most part, I think the crisis in the Philippines was largely man-made—the external shocks merely exposed them," Ateneo Dean Ronald Mendoza said in an online interview with Philstar.com.

Filipinos today are able to look back and understand what happened, but in those years even the experts misinterpreted the signals of an impending crisis by the end of 1983.

Myth: Aquino's assassination to blame

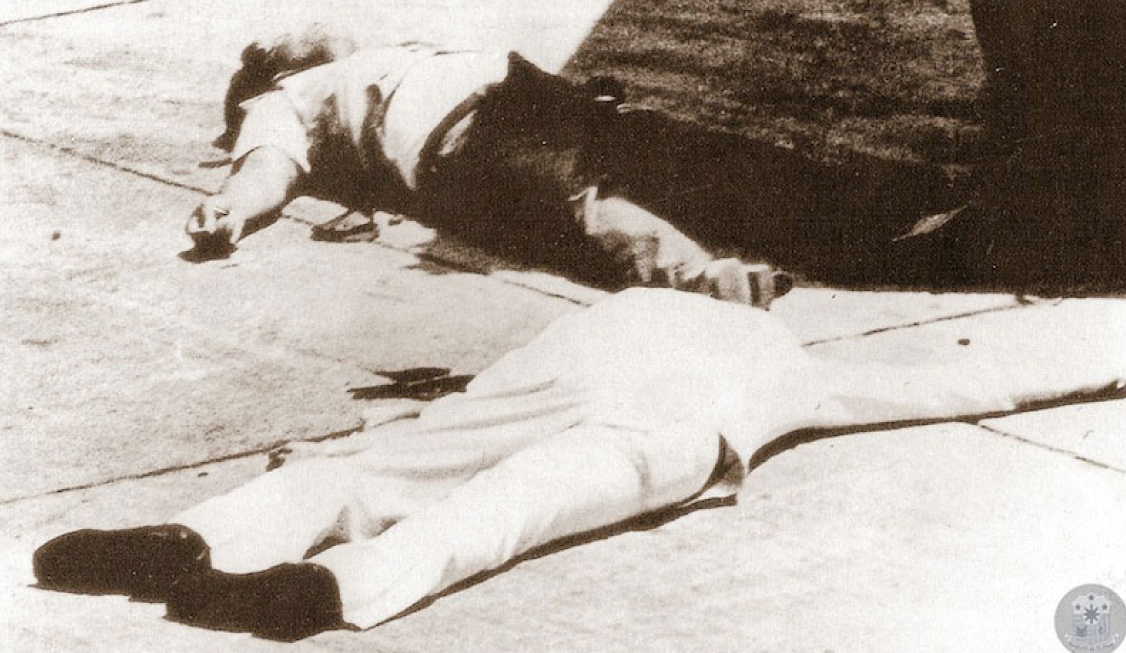

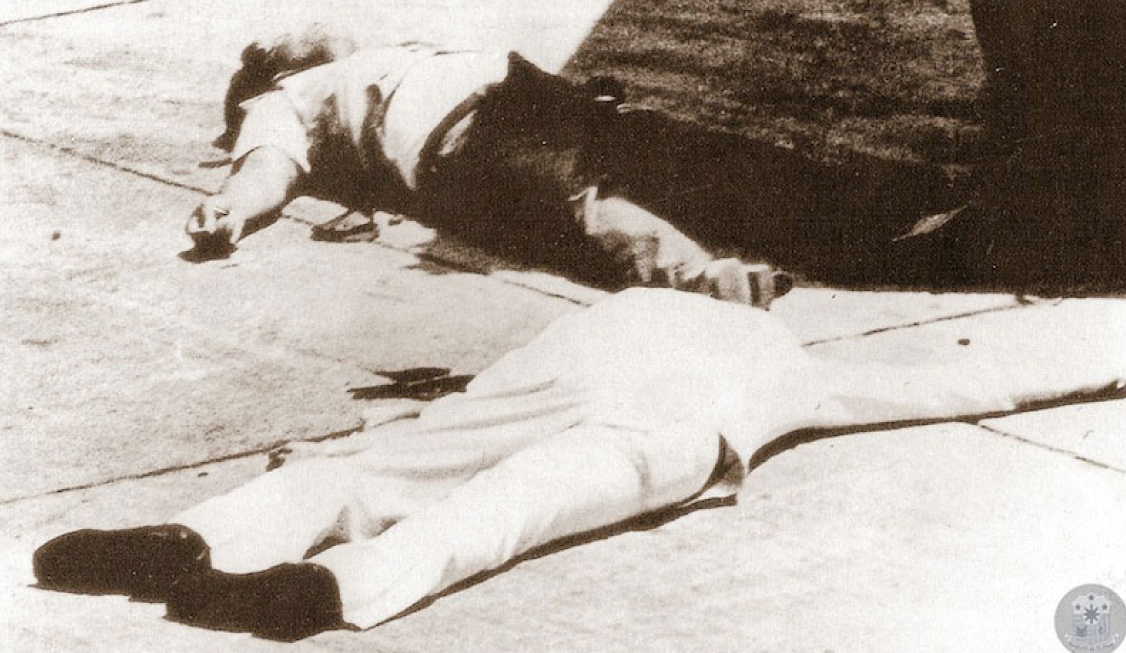

In 1983, Aquino, the staunch Marcos critic, returned to the Philippines from exile and was killed on the tarmac as he alighted from the plane. As a result, foreign banks lost confidence in the regime and refused to grant further borrowings, De Dios wrote. This explains why Martial Law advocates to this day blame Aquino's return and death for economic misfortunes in the latter Marcos years.

"All it took was a crisis to expose these weaknesses and for the facade of democracy to unravel."

— Ronald Mendoza, economist

For Mendoza, the senator's assassination played a role in triggering "what was already a simmering political and economic crisis."

"But if it wasn't the assassination of Ninoy, it would have been something else, perhaps."

The economist said the weakening of institutions under Marcos had by then taken its toll. The institutional cracks included the lack of independence of the central bank, weaknesses in competitive bidding for government projects, rent-seeking and cronyism in government subsidies for industrial policy and outright plunder of the public purse.

"All it took was a crisis to expose these weaknesses and for the facade of democracy to unravel," Mendoza said.

Spoils of dictatorship

Tasked to recover what was believed to be the strongman's hidden wealth, the Philippine Commission on Good Government set to work by going after agents working for Marcos in the Philippines and abroad. The PCGG was among the first bodies President Corazon Aquino formed after Marcos was overthrown through "people power."

The Jovito Salonga-led commission uncovered a trail to what appeared to be vast assets of Marcos "stretching from a small Texas motel to a San Francisco bank, from a glitzy Manhattan shopping mall to a block of apartment buildings in downtown Seattle," the Los Angeles Times reported in 1986.

As president, Marcos earned a yearly salary of $4,700 or about P100,000, and was not part of the traditional elite before becoming a politician. How he came to be worth billions of dollars by the end of his rule was seen as a sign of how he used martial law to line his pockets.

As dictator, Marcos wrote letters of instruction and decrees to position his cronies—as his associates came to be called—to set up monopolies of key industries. Even as he gained popular support for attacking the ruling class he called the "oligarchy," Marcos ironically created a loyal new elite controlling the country's largest enterprises.

"Some are smarter than others," Marcos' wife, Imelda, famously answered when Fortune magazine asked her about relatives and friends who grew rich during the period.

Loyal Marcos backer Roberto Benedicto took over the lucrative sugar industry, while Eduardo Cojuangco led a powerful crony corporation sitting on taxes from coconut farmers. "By the 1980s, the 'coco levy' would become one of the major issues against the dictatorship, the term connoting its most rapacious aspects," wrote business journalist Rigoberto Tiglao in 1988.

Historian Alfred McCoy said Imelda's brother, Benjamin Romualdez, took control of P5.7 million in holdings of the influential Lopez family, including the largest power distributor Meralco, newspapers and television studios, for a mere $1,500.

Marcos allowed a handful of families to cinch monopolies and semi-monopolies in manufacturing, construction, finance and other important sectors of the economy, which were even favored with tax cuts and other privileges. When these select corporations proved unprofitable and inefficient, the government loaned millions to keep them going.

The massive bailouts for failed crony businesses and the earnings from sugar and coconut exports placed in foreign banks were critical factors leading to another economic disaster. While this caused much resentment among a portion of the business community, it was the most vulnerable and voiceless that were hit the hardest.

After all, many of the crony business leaders continued to hold levers of power even after the dictator was deposed in 1986, Canada-based economist Polvorosa observed.

The captain at the helm not only caused the ship to sink, he also managed to swim away with a sizeable loot for himself.

And the poor were poorer

Myth: 'Mas madali ang buhay noon'

Women started to seek jobs in the mid-1970s due to the decline in their husbands' income.

Some Filipinos today recall that life was "simpler"—even better—during Marcos's years. But these anecdotes are nowhere reflected when looking at the hard data on the population's welfare.

About 42 percent of Filipinos were considered poor in the 1960s when Marcos rose to power. In 1971, the year before Marcos declared martial law, poverty incidence rose to 52 percent. By the time Marcos approached the end of his 21-year rule, already three of five Filipinos (59 percent) were poor.

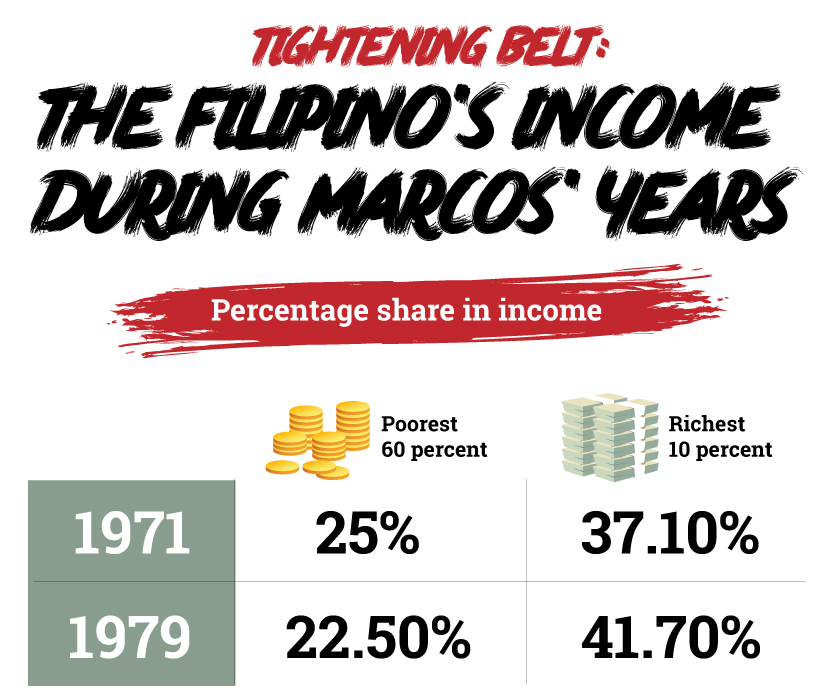

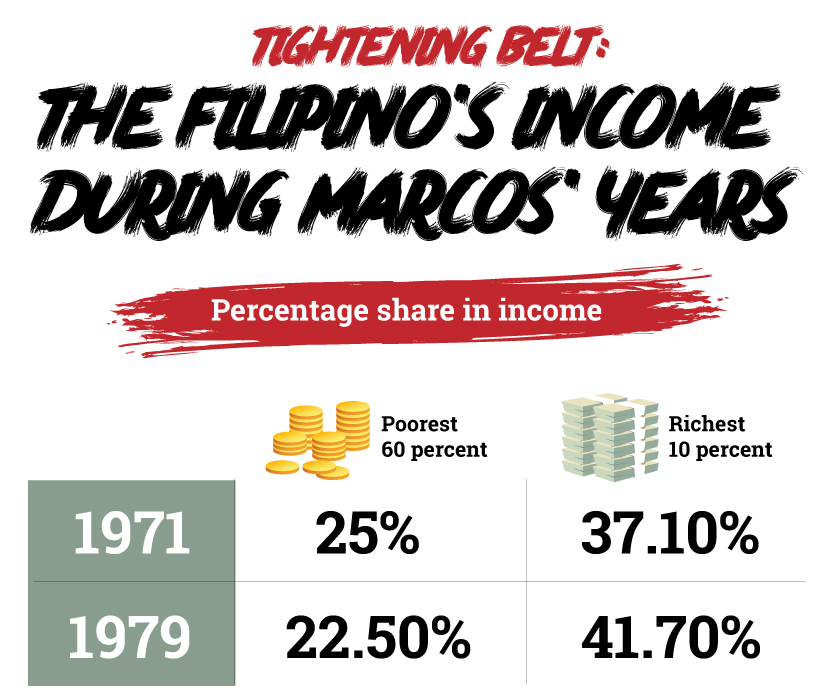

Income distribution also worsened during Martial Law, with the poorest segment of society seeing a decline in their share of the total income between 1971 and 1979. The richest 10 percent, on the other hand, enjoyed a much larger piece of the pie.

Shifts in employment in those years get even interesting. De Dios and fellow economists observed an "unusually high" expansion of labor supply, or the number of people available for work.

This was due to housewives who started to seek jobs in the mid-1970s—a phenomenon attributed not necessarily to women empowerment, but to the decline in husbands' income below what used to be enough for their families' subsistence.

The economy today is dramatically better than the Marcos economy; but without inclusion, many of our citizens probably can't tell the difference.

— Ronald Mendoza, economist

From 1978 to 1983, the number of workers without jobs increased from 800,000 to 1.2 million. But the figure for underemployment was more shameful, going from 1.6 million to 5.6 million.

How people could afford goods also suffered from dramatic swings in inflation. While an annual inflation rate of 1 to 4 percent is considered respectable today, in the 1970s, it sprang to double digits.

This was partly ascribed to roiling external conditions, but a comparison of the Philippines' performance with those of its neighbors suggests that high inflation rate and lower economic growth "could have been avoided and could be attributed, not to the general problems of a developing country, but to the character of the policies of the present government," De Dios and colleagues explained in 1984.

If a critical measure of an economy's performance is its trickle-down effect, then the Martial Law enablers miserably failed.

Challenges of inclusion, however, continue to this day. For Dean Ronald Mendoza, this has likely made the Marcos prosperity myth endure for decades even when the economy has grown dramatically better.

"I think the Marcos myth persists largely because we have failed to effectively push in the Post-Marcos era the key or deep institutional reforms, notably political and economic reforms that could make our politics and economy much more inclusive," Mendoza explained.

"Understandably, many are tempted by shortcuts and strongman rule, instead of faithfully building the institutions that could strengthen our democracy and economy.

"The economy today is dramatically better than the Marcos economy; but without inclusion, many of our citizens probably can't tell the difference," he added. — Philstar.com NewsLab with reports from Audrey Morallo

Shortly after academics slammed his "revisionist" view, defeated vice presidential aspirant Bongbong Marcos denied having said that the years of his father, the dictator Ferdinand, were the Philippines' golden age. But on the campaign trail last year, Marcos Jr. did fuel the myth by praising his father's "good work" which for him continues to benefit the people.

The prosperity myth has endured for decades despite a peaceful revolution that drove the autocrat from power. Marcos supporters usually back their view with mini-narratives on the narrow peso-to-dollar conversion rate, growth in early Marcos years, free-flowing traffic, enthusiastic government spending and the country's regional competitiveness, among others.

Experts such as Cesar Polvorosa Jr. of Canada's Humber Business School say, however, that economic performance under any given administration should be measured by the sustainability of growth and its benefits to the general population.

"Other aspects of economic policymaking simply follow from those two major issues. Promoting economic growth enhances employment and livelihood opportunities," Polvorosa wrote last year.

THE EC NOMY

NOMY

UNDER MARCOS

-1960'S-

Marcos assumed

presidency

Campaign period (Overspending, raiding of public treasury)

Export became

sluggish

ISI stagnant

Reelection

of Marcos

Balance of

payments crisis

Devaluation,

fueled inflation

-1970'S-

Martial law

Incoherent

development

strategies

Promotion

of exports

Protection of

ISI firms

External funds for

borrowing remained

available

Debt-driven growth

(foreign loans sustained growth)

Centralized,

longer term control

over state apparatus

-1980'S-

Economic crisis

intensified after

assassination of Aquino

Crony abuses

brought economic

disaster

IMF becomes vengeful

God and limits

Philippines' borrowings

Unpopularity

of the regime

*Based on 'The Philippine Economy: Development, Policies and Challenges' (2003) by Arsenio Balisacan and Hall Hill, Oxford University Press

Retelling the tragedy necessarily starts with a picture of the economy in a dismal state, worse than it had ever been, in the years leading to the ouster of the Marcos family in 1986. It is a story of debt, deprivation and the spoils of a dictatorship.

Debts and downturns

The country was deep in debt—owing $24 billion by 1984 to be exact—with major businesses having absorbed much funding despite lacking in productivity. Massive government construction projects remained either unfinished or without immediate socioeconomic yield. There was a broad gap in incomes of the richest and poorest, while prices of goods skyrocketed. Only a few families controlled and benefited from key industries. The list went on.

Economists from the University of the Philippines led by Emmanuel de Dios sought answers on the crisis felt then. Was it mainly an effect of external shocks, as Marcos supporters claimed? Was it because of the assassination of opposition leader Sen. Ninoy Aquino in 1983? Or was the downturn primarily due to Marcos' policies and abuses?

They found all three factors playing a role, but the explanation that best satisfied their inquiries pointed to a concentration of power in government and its economic policies that dug deeper and deeper holes.

"While the Philippines experienced more or less the same external shocks as other developing countries, there is a residual variation in its performance and response which makes it fall below the average for countries in its class," they wrote.

Needless to say, the economy did not simply sink overnight.

Myth: The region's powerhouse

In the 1950s, the Philippines was second to Japan in terms of per capita income in the region. The country enjoyed moderate economic growth alongside its neighbors while focusing on imports. A common anachronism today's apologists commit is to label this relatively prosperous time part of the "Marcos period."

Marcos assumed the presidency only in 1965, when things started to spiral downward in the late 1960s as existing policies no longer encouraged rapid growth. The would-be dictator then pursued an aggressive, expensive run for a second term by foraying into the public treasury to boost his campaign, buy votes and threaten voters. The peso crashed in late 1969, and by the dawn of the following year it lost half its value, Conrado de Quiros wrote in "Dead Aim."

The 1960s crisis, for economists Arsenio Balisacan and Hall Hill, "was triggered by one politician's particularly shameless efforts to maintain a grasp on the reins of the political machinery."

Among its peers, the country could no longer keep up. "While the Philippines started with the highest growth rates for [Southeast Asia] in 1950-1960 (3.6 percent annually), it lagged behind its neighbors in 1960-1970," economists De Dios, Dante Canlas, Solita Monsod and their fellow U.P. economists wrote.

THEN AND NOW:

HOW MARCOS' YEARS COMPARE

Source: * An Analysis of the Philippine Economic Crisis' (1984) edited by Emmanuel de Dios, University of the Philippines; World Development Indicators

To deal with external shocks and a campaign spree that ingested ridiculous amounts in the guise of government projects, the country resorted to debt, and according to the U.S. Library of Congress, was behind by $2.3 billion in payment due in the early 1970s. Then came a pattern of chronic borrowing, devaluation of the peso which bloated prices of goods, and reckless spending.

Myth: A spectacular economy and showmanship

More debts were incurred to pay outstanding debts and to stimulate the economy. The debt-fueled boom in the early 1970s coupled with sweeping reforms and infrastructure programs deceived many, providing the semblance of stability Marcos needed to calm the business elite after he placed the country under martial law.

"The trouble with debt-driven growth with populist tendencies is that it produces a buoyant economic environment—at least in the beginning. As long as the facade of investment for competitiveness is still there, then investors continue to pour money into the economy, which keeps it growing," Harvard-trained economist Ronald Mendoza, dean of the Ateneo School of Government, explained to Philstar.com.

"Initially, it looks very good," Mendoza admitted. "It doesn't take rocket science to figure out that the country's debt-driven growth was a party that would soon end, once investors figured out that despite the mounting debt, the country failed to effectively invest in key infrastructure and competitiveness-enhancing projects."

The 1970s saw the kind of progress without momentum. As then Social Security System chief Adrian Cristobal told Harvard University fellow William Overholt, "It was like an old lady taking off her girdle. Everything just fell out."

The regime's initial reforms turned upside down as institutions bowed to corruption, red tape, inefficiency and Marcos-led cronyism. His development strategies and trade policies were likewise incoherent, not to mention the padding of debt mainly for a gamut of projects that required large funding despite little gain.

Overholt said these included hosting of ostentatious international meetings. International Monetary Fund delegates, for example, were each assigned a brand new Mercedes Benz that was afterward sold as a second-hand car.

The wastefulness could not be exaggerated. Explaining the capital-output ratio at the time, Overholt said it was typical for Asia-Pacific countries to spend $2 to $4 to raise national output by $1. But the Philippines was spending $9 for every buck.

It was typical for Asia-Pacific countries to spend $2 to $4 to raise national ouput by $1. But the Philippines was spending $9 for every dollar.

Debt climbed to $17.2 billion by 1980, and the rate of gross national product—which measures the total value of production—took a dive. Already crippled, the Philippines was gasping for air when world recession hit and its exports suffered way worse than those of its neighbors.

"External factors could help trigger a crisis; but domestic fundamentals (or the lack of it) will dictate resilience to these external shocks. For the most part, I think the crisis in the Philippines was largely man-made—the external shocks merely exposed them," Ateneo Dean Ronald Mendoza said in an online interview with Philstar.com.

Filipinos today are able to look back and understand what happened, but in those years even the experts misinterpreted the signals of an impending crisis by the end of 1983.

Myth: Aquino's assassination to blame

In 1983, Aquino, the staunch Marcos critic, returned to the Philippines from exile and was killed on the tarmac as he alighted from the plane. As a result, foreign banks lost confidence in the regime and refused to grant further borrowings, De Dios wrote. This explains why Martial Law advocates to this day blame Aquino's return and death for economic misfortunes in the latter Marcos years.

"All it took was a crisis to expose these weaknesses and for the facade of democracy to unravel."

— Ronald Mendoza, economist

For Mendoza, the senator's assassination played a role in triggering "what was already a simmering political and economic crisis."

"But if it wasn't the assassination of Ninoy, it would have been something else, perhaps."

The economist said the weakening of institutions under Marcos had by then taken its toll. The institutional cracks included the lack of independence of the central bank, weaknesses in competitive bidding for government projects, rent-seeking and cronyism in government subsidies for industrial policy and outright plunder of the public purse.

"All it took was a crisis to expose these weaknesses and for the facade of democracy to unravel," Mendoza said.

Spoils of dictatorship

Tasked to recover what was believed to be the strongman's hidden wealth, the Philippine Commission on Good Government set to work by going after agents working for Marcos in the Philippines and abroad. The PCGG was among the first bodies President Corazon Aquino formed after Marcos was overthrown through "people power."

The Jovito Salonga-led commission uncovered a trail to what appeared to be vast assets of Marcos "stretching from a small Texas motel to a San Francisco bank, from a glitzy Manhattan shopping mall to a block of apartment buildings in downtown Seattle," the Los Angeles Times reported in 1986.

As president, Marcos earned a yearly salary of $4,700 or about P100,000, and was not part of the traditional elite before becoming a politician. How he came to be worth billions of dollars by the end of his rule was seen as a sign of how he used martial law to line his pockets.

As dictator, Marcos wrote letters of instruction and decrees to position his cronies—as his associates came to be called—to set up monopolies of key industries. Even as he gained popular support for attacking the ruling class he called the "oligarchy," Marcos ironically created a loyal new elite controlling the country's largest enterprises.

"Some are smarter than others," Marcos' wife, Imelda, famously answered when Fortune magazine asked her about relatives and friends who grew rich during the period.

Loyal Marcos backer Roberto Benedicto took over the lucrative sugar industry, while Eduardo Cojuangco led a powerful crony corporation sitting on taxes from coconut farmers. "By the 1980s, the 'coco levy' would become one of the major issues against the dictatorship, the term connoting its most rapacious aspects," wrote business journalist Rigoberto Tiglao in 1988.

Historian Alfred McCoy said Imelda's brother, Benjamin Romualdez, took control of P5.7 million in holdings of the influential Lopez family, including the largest power distributor Meralco, newspapers and television studios, for a mere $1,500.

Marcos allowed a handful of families to cinch monopolies and semi-monopolies in manufacturing, construction, finance and other important sectors of the economy, which were even favored with tax cuts and other privileges. When these select corporations proved unprofitable and inefficient, the government loaned millions to keep them going.

The massive bailouts for failed crony businesses and the earnings from sugar and coconut exports placed in foreign banks were critical factors leading to another economic disaster. While this caused much resentment among a portion of the business community, it was the most vulnerable and voiceless that were hit the hardest.

After all, many of the crony business leaders continued to hold levers of power even after the dictator was deposed in 1986, Canada-based economist Polvorosa observed.

The captain at the helm not only caused the ship to sink, he also managed to swim away with a sizeable loot for himself.

And the poor were poorer

Myth: 'Mas madali ang buhay noon'

Women started to seek jobs in the mid-1970s due to the decline in their husbands' income.

Some Filipinos today recall that life was "simpler"—even better—during Marcos's years. But these anecdotes are nowhere reflected when looking at the hard data on the population's welfare.

About 42 percent of Filipinos were considered poor in the 1960s when Marcos rose to power. In 1971, the year before Marcos declared martial law, poverty incidence rose to 52 percent. By the time Marcos approached the end of his 21-year rule, already three of five Filipinos (59 percent) were poor.

Income distribution also worsened during Martial Law, with the poorest segment of society seeing a decline in their share of the total income between 1971 and 1979. The richest 10 percent, on the other hand, enjoyed a much larger piece of the pie.

Shifts in employment in those years get even interesting. De Dios and fellow economists observed an "unusually high" expansion of labor supply, or the number of people available for work.

This was due to housewives who started to seek jobs in the mid-1970s—a phenomenon attributed not necessarily to women empowerment, but to the decline in husbands' income below what used to be enough for their families' subsistence.

The economy today is dramatically better than the Marcos economy; but without inclusion, many of our citizens probably can't tell the difference.

— Ronald Mendoza, economist

From 1978 to 1983, the number of workers without jobs increased from 800,000 to 1.2 million. But the figure for underemployment was more shameful, going from 1.6 million to 5.6 million.

How people could afford goods also suffered from dramatic swings in inflation. While an annual inflation rate of 1 to 4 percent is considered respectable today, in the 1970s, it sprang to double digits.

This was partly ascribed to roiling external conditions, but a comparison of the Philippines' performance with those of its neighbors suggests that high inflation rate and lower economic growth "could have been avoided and could be attributed, not to the general problems of a developing country, but to the character of the policies of the present government," De Dios and colleagues explained in 1984.

If a critical measure of an economy's performance is its trickle-down effect, then the Martial Law enablers miserably failed.

Challenges of inclusion, however, continue to this day. For Dean Ronald Mendoza, this has likely made the Marcos prosperity myth endure for decades even when the economy has grown dramatically better.

"I think the Marcos myth persists largely because we have failed to effectively push in the Post-Marcos era the key or deep institutional reforms, notably political and economic reforms that could make our politics and economy much more inclusive," Mendoza explained.

"Understandably, many are tempted by shortcuts and strongman rule, instead of faithfully building the institutions that could strengthen our democracy and economy.

"The economy today is dramatically better than the Marcos economy; but without inclusion, many of our citizens probably can't tell the difference," he added. — Philstar.com NewsLab with reports from Audrey Morallo