One of the most persistent myths about the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos was on the flourishing and vibrancy of democracy during his time. Some even claim that democracy was at its peak when he was president.

This myth, however, misses reality by miles.

From employing vicious terrorism and violence during elections to the militarization and "Ilocanization" of the bureaucracy, the record of the dictator could be described as anything but democratic.

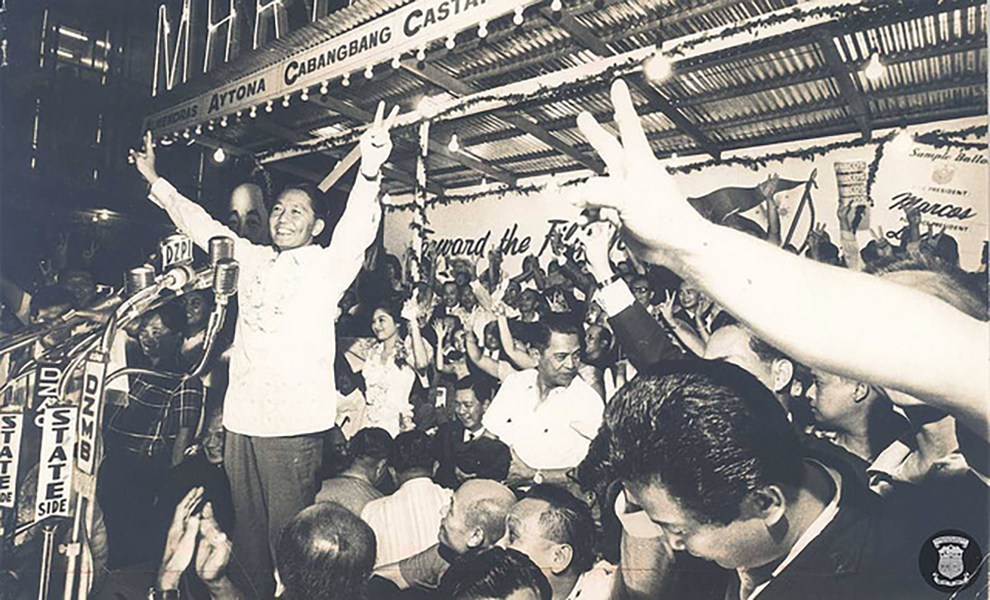

Ferdinand Marcos always believed himself to be a man of destiny, a heroic figure who would save the Philippines from the morass of poverty, conflict and violence it was mired with.

In his book "Dead Aim: How Marcos Ambushed Philippine Democracy," Conrado de Quiros said Marcos combined personal ambition with national interest and the divine to give his actions—in his mind—a sense of obligation and inexorability.

Although he believed himself to be a heroic figure, he still displayed a propensity to embellish things, which could be partly explained by his need to be seen as head and shoulders above everyone else.

However, even if Marcos had great faith in his destiny as the "liberator" of the Philippines from the stasis it experienced in its post-war politics, he still believed in giving destiny a hand, and this was where his assault on the country's democracy was at its most pernicious.

Election of 'guns, goons and gold'

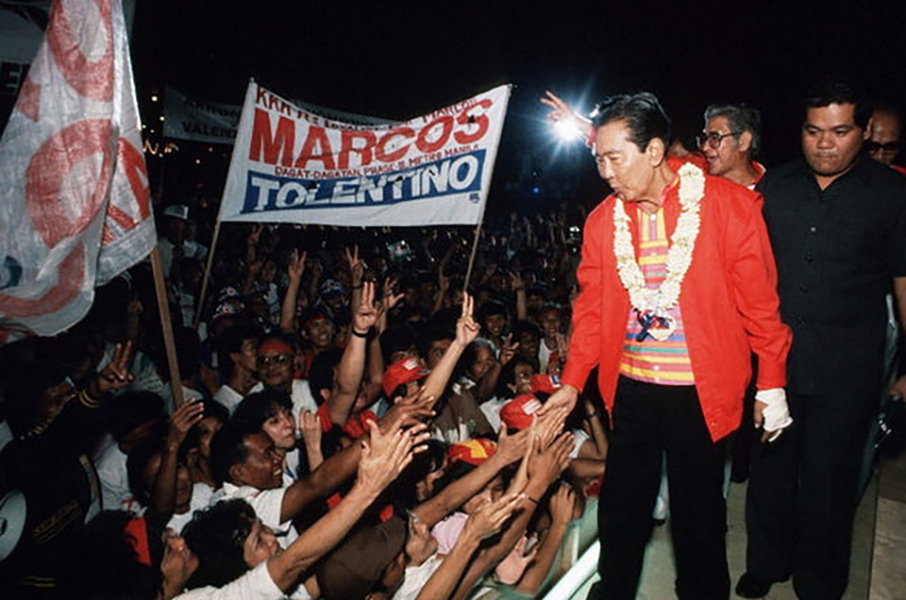

According to De Quiros, Ferdinand Marcos employed during his time the infamous three Gs: "Guns, Goons and Gold."

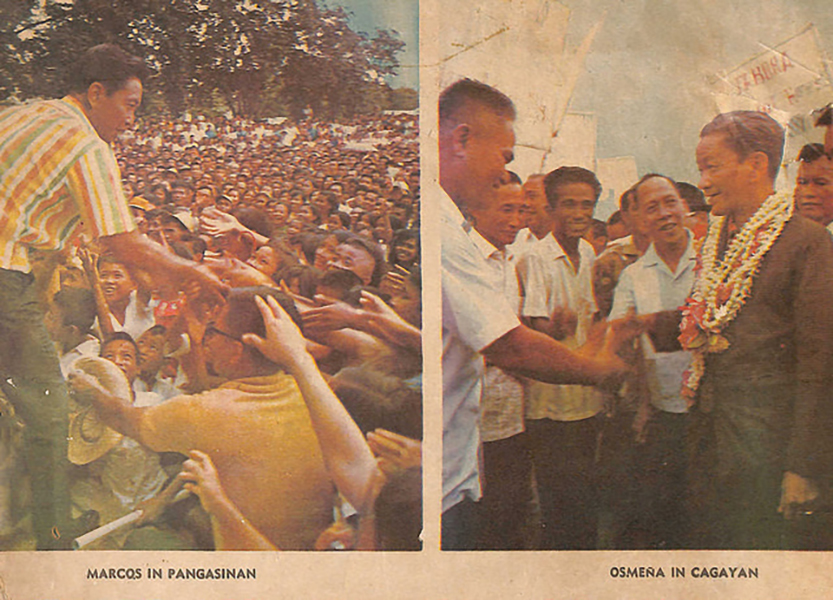

In 1969, for instance, Marcos defeated Sergio Osmena Jr. by employing vote-buying, terrorism and ballot snatching. Marcos used the "pork barrel" in his presidential bid that year, setting a new precedent in patronage politics. In Cebu alone, he spent P24 million in pork on top of the P1 billion he expended to get reelected.

In "Dead Aim," Sen. Benigno Aquino said that for every P1 that Osmena spent, Marcos spent P100. Because of this heavy campaign spending, the peso crashed to nearly P4 to in February 1970 from P2 to before the November 1969 polls.

Among the most brazen electoral terrorism was done by the Philippine Constabulary. In Batanes, its officers, paramilitary groups and hoodlums took over the entire island and allowed thugs in Suzuki motorcycles to terrorize voters and Comelec officials and beat up opposition leaders.

All these led Time and Newsweek to call the 1969 election the "dirtiest, most violent and most corrupt" in Philippine modern history.

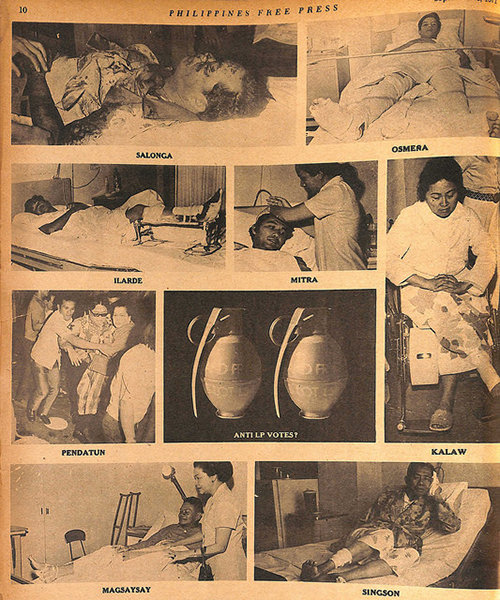

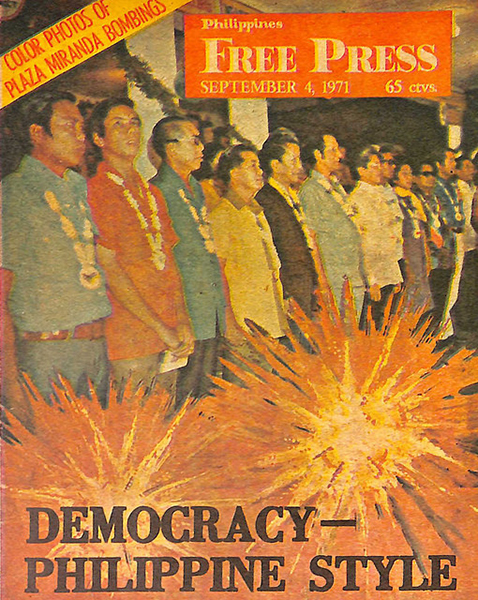

Another case of brutal electoral violence the country witnessed was the bombing of the miting de avance of the Liberal Party on Aug. 21, 1971.

The Liberal Party was the main opposition party to the rule of Marcos. Before the 1971 elections, the Liberals faced years of electoral abyss. In 1965, they lost not only the presidency but also the Senate. That year, only two Liberals of the eight voted during that election cycle won—Sergio Osmeña Jr. and Jovito Salango, who topped that race.

The 1967 polls proved even worse for the LP. Only one Liberal managed to make it to the Senate that year, and his name was Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr. He was almost booted out of the Senate because of allegations of being underage, but fortunately for him he had a good lawyer by his side, Jovito Salonga who lost no time to prove why he once topped the bar examination, according to De Quiros.

The fortunes of the LP did not change in 1969. Their candidate for the presidency, Osmeña Jr., lost, and Marcos became the first president to get reelected after the Great War. That cycle, only two Liberals managed to get to the Senate.

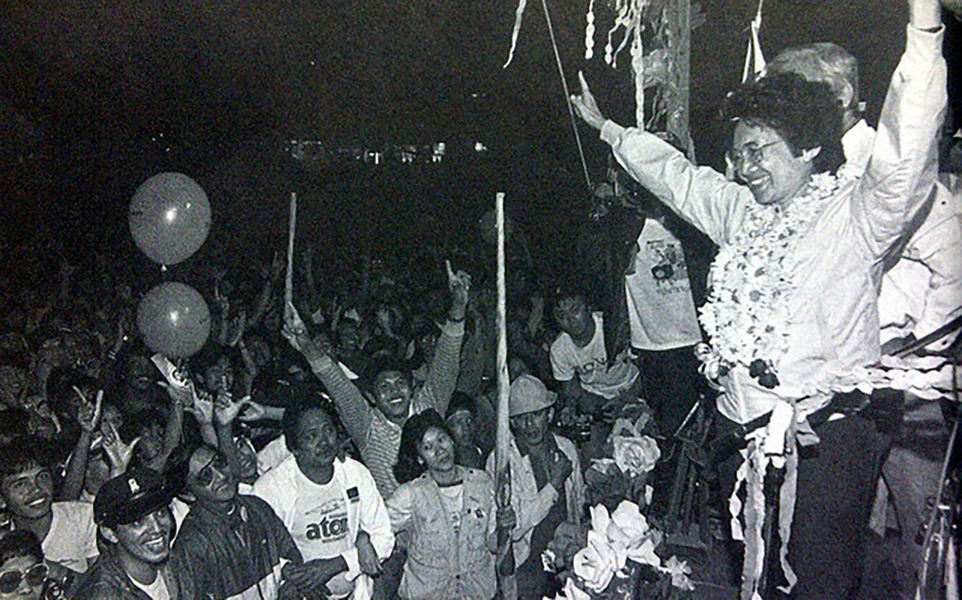

The direction of the wind, however, began to change in 1971. De Quiros said that the Liberals could already feel the presidency, and the 1971 elections were a prelude to their impending victory in 1973. On the night of Aug. 21, 1971, the Liberals prepared to start their journey back to Malacañang.

Their miting de avance at Plaza Miranda was meant to be a show of force both by local and national candidates. The candidates condemned to high heavens the abuses and excesses of Marcos. Everybody was in high spirits, and they thought that their political rally that night was the start of a political comeback that would end with an electoral bang.

Little did they know that a literal explosion would rip through Plaza Miranda.

That night, nine people were murdered and almost a hundred hurt. All the LP senatorial bets, except Aquino, were hurt. Osmeña was pronounced to be in critical condition while Salonga's body was peppered with more than 100 pieces of metal.

The injured, the widowed, the media, the Catholic Church and other victims of the bombing had one person in mind on who perpetrated the bombing: Ferdinand Marcos.

Legal veneer for martial law

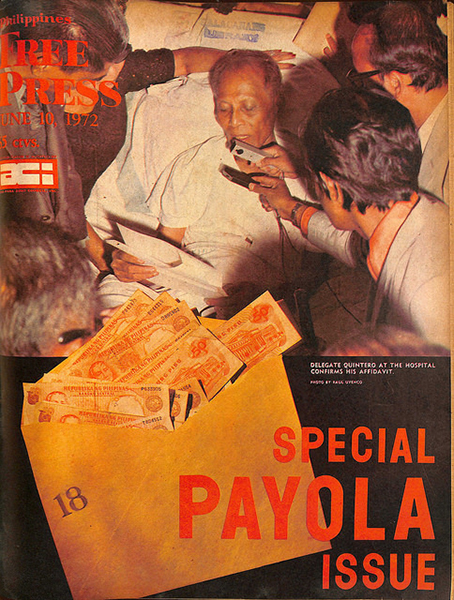

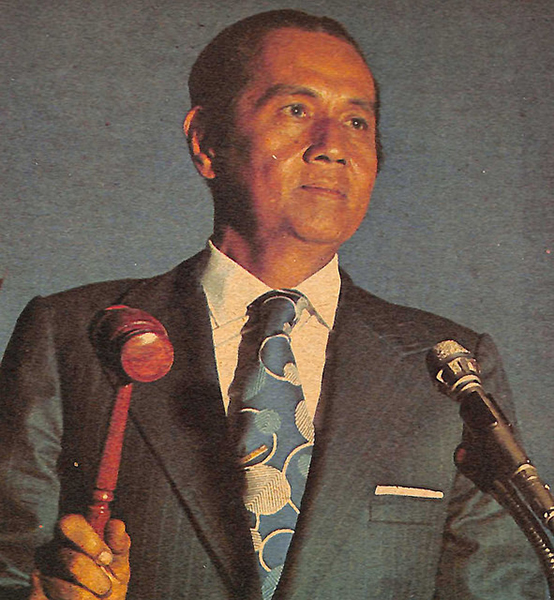

Probably because of his legal background, Marcos had to give his actions a facade of legality. Some would say that this was even his propensity. Rigged referendums and elections were his main tools to achieve this.

Marcos engineered the ratification of the 1973 Constitution by using his appointed village chairmen to report that the people approved the new charter by raising their hands. Television footage showed people raising their hands in affirmation, but this was because they were asked who among them would like to have a regular ration of rice.

Before the 1973 referendum, Malacañang tried to bribe delegates to the 1970 Constitution Convention, as exposed by Eduardo Quintero, a delegate from Leyte.

The dictatorship conducted another referendum in 1977 and elections for the Interim Batasang Pambansa in 1978 to show that he had the mandate from the people. In all these, Marcos got the votes, and in one instance got a statistically improbable 99 percent.

He also assaulted the Supreme Court using carrot and stick methods. Marcos was able to force the high court to uphold his rule (even to the extent of forging the opinion of one justice) and the constitutionality of Martial Law in Aquino vs. Enrile, according to Rigoberto Tiglao in a chapter that he wrote in the book "Dictatorship and Revolution."

Militarization for 'peace and order'

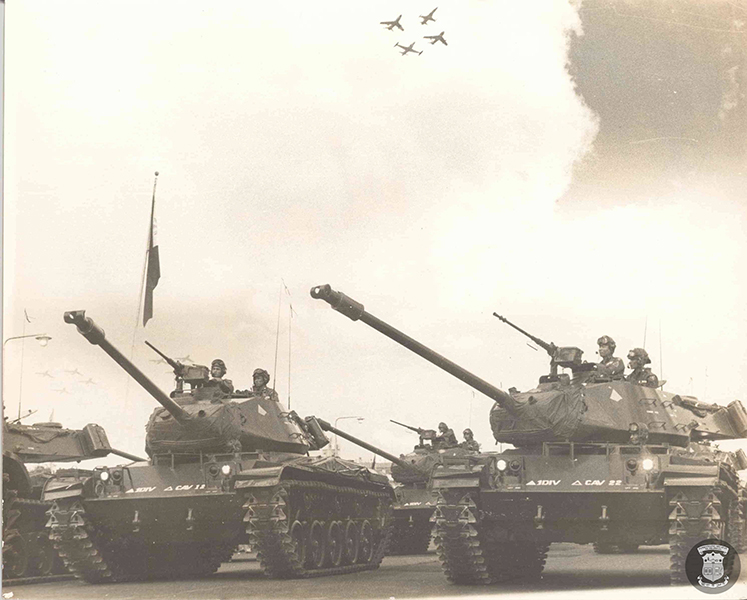

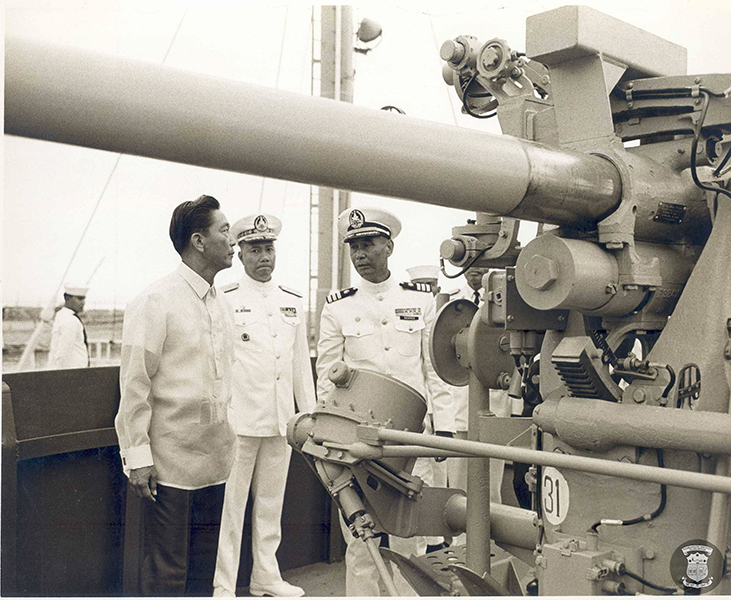

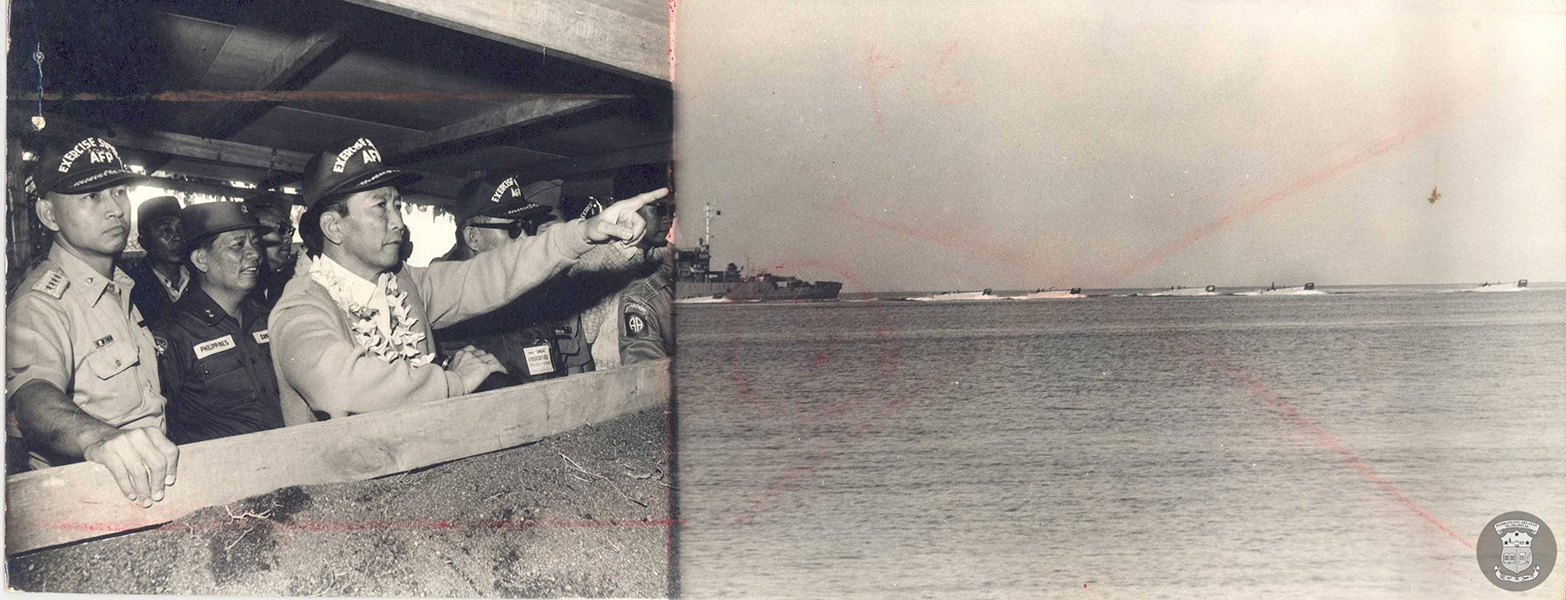

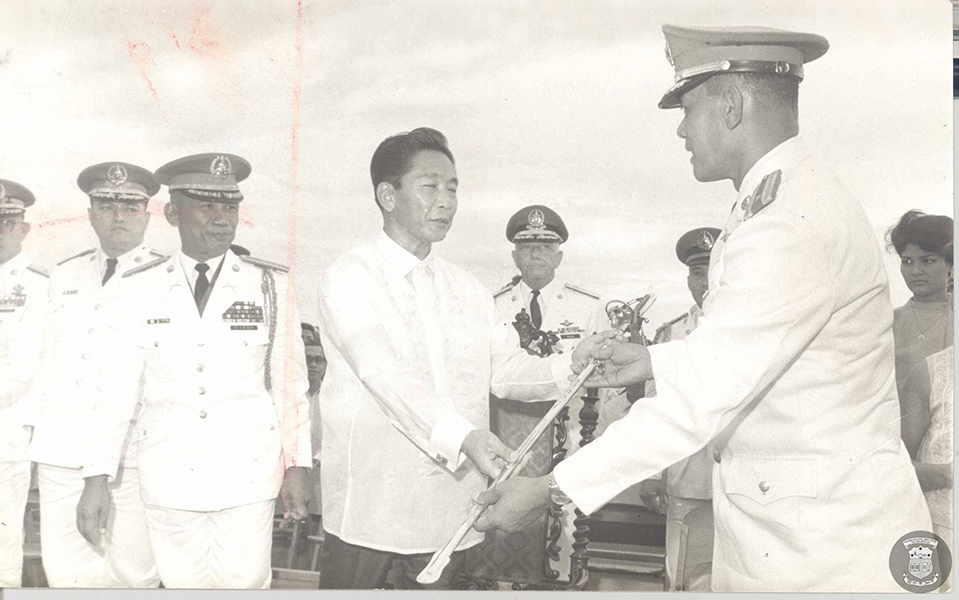

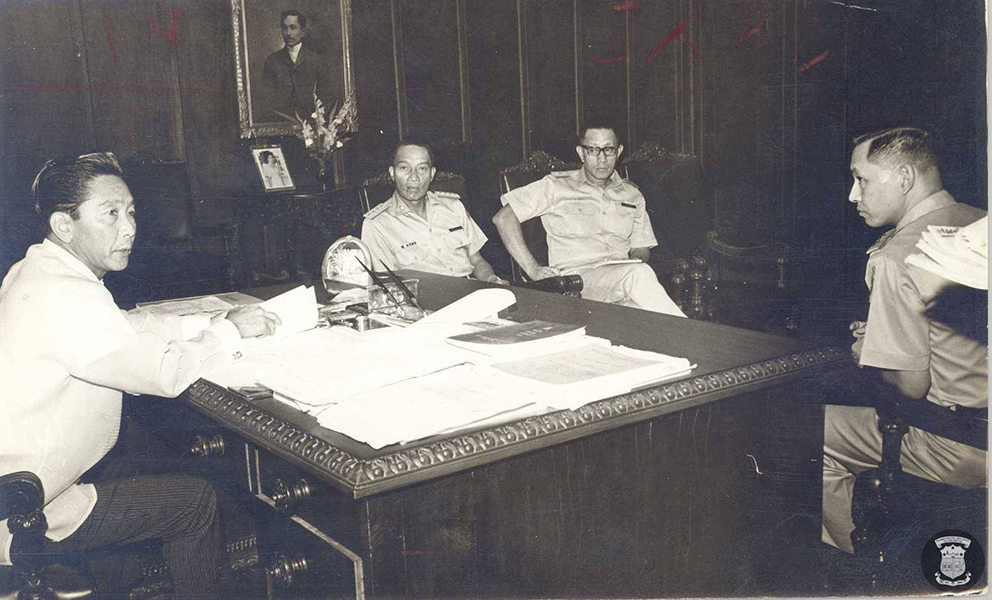

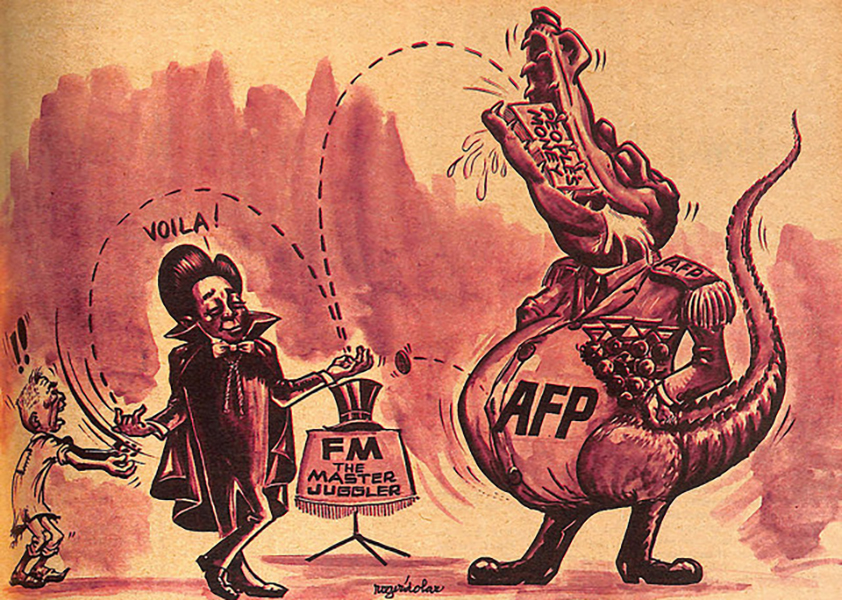

The military was the locus of power during Martial Law. It was the keeper of "peace" and "order." To concentrate power, Marcos harnessed the military to the utmost.

To achieve this, the dictator showered the military with blessings. Even before he became president, he was already a champion of the military by fighting for the Armed Forces budget and campaigning for the promotion of his favorite officers in Congress.

Upon becoming president, he increased the Armed Forces of the Philippines' (AFP) budget. During Martial Law, it ballooned to P4 billion in 1976 from P880 million in 1972, based on Tiglao's monograph. Troop size also increased from 60,000 in 1972 to 250,000 in 1975.

As a demonstration of how central the military is in his rule, Marcos utilized the military for functions formerly reserved for the civilian bureaucracy such as doing community work. This brought them in contact with politicians and gave them the chance to see they had the potential, even moral obligation, to run the country in the face of inefficiencies of the civilian government.

The military's main function in the Marcos government, however, was in nipping through violence dissent and actions that could threaten the dictatorship, and most of the most ruthless violence transpired in the countryside. The special and paramilitary forces raised their scale of political violence in the provinces, literally turning the AFP into Marcos' private army. He also allowed the private armies of his supporters such as the Crisologos of the North and the Duranos of Cebu to operate.

The reign of terror of the military during the Marcos regime was so widespread and systematic that international and human rights watchdogs such as Amnesty International lost no time criticizing the abuses in the Philippines. The military generated havoc in communities suspected of being communist infiltrated even without evidence. Many abuses were committed by paramilitary groups in the name of national security.

A bust of Ferdinand Marcos near Baguio as seen in 1989. It was partially destroyed in 2002.

Photo by Angust/CC BY-NC

In extreme cases, whole families such as the Hilao family were the subject of abuse and brutality. Seven members of the family were arrested and detained, including a seven-year-old child. Winifredo was severely tortured, and Liliosa was raped, tortured and murdered after Martial Law was declared.

Aside from his support, Marcos instilled loyalty and kinship with the soldiers by making it appear that he was one of them through his questionable medals. In the case of generals and military officers he could not rely on, Marcos retired them or sent them abroad for ambassadorships as in the case of Manuel Yan, who became the envoy in Thailand after his military stint.

'Ilocanization' of government

Tiglao wrote that 18 out of the 22 generals of the Philippine Constabulary were from the Ilocos region. The Metropolitan Command (Metrocom), the first infantry in Fort Magsaysay and Task Force Lawin were also heavily Ilocano. In addition, a vast intelligence network was placed under the command of Gen. Fabian Ver, a known loyal Marcos relative.

The "Ilocanization" of the military was symptomatic of the preponderance of Ilocano politicians, or Northern politicians as Marcos called them, in his government. This enabled Marcos to have individuals who were blindly loyal to him to man the military. This precluded dissenting voices and ideas from emerging. More importantly, this enabled Marcos to consolidate his grasp of the Armed Forces.

Marcos filled government posts with Ilocanos whom he had known since the days when he built his network of allies from his hometown. He preferred his province mates over other individuals for a simple reason: The Ilocanos were fiercely loyal to him.

De Quiros explained that in Ilocos there was this strong patron-client relationship or the very concept of family. In this setup, Marcos provided for the region but in return demanded fealty from it. Any "errant" subordinate was cut down to size, usually in public.

Debt-driven growth and support of the elite

Tiglao said the Marcos regime took advantage of the country's "credit-worthiness" arising from its balance-of-trade, the difference between a country's imports and exports. The government heavily borrowed partly to finance infrastructure projects that would provide artificial stimulus to the country and the growth of the Philippine ruling class that would be absolutely loyal to him- — -- his "cronies."

The infrastructure spending enabled the Marcos regime to build up a semblance of prosperity and peace to court the support of the middle and upper classes. The seeming efficiency of the dictatorship in its first few years also led the elite to support it. Strikes were banned, which proved beneficial for the upper class, and the "climate of anarchy" that pervaded in the early 70s was quickly extinguished, at least on the surface.

The first few years of Martial Law proved economically beneficial for the elite, which led them to support martial rule. According to Tiglao, the profits of the country's top 1,000 corporations jumped from P1.3 billion in 1972 to P3.02 billion in 1973 and to P3.5 billion in 1975. This period for the elite provided a favorable business climate.

The support of the middle and upper classes was crucial in Marcos' effort to consolidate his dictatorship.

The support of the middle and upper classes was crucial in Marcos' effort to consolidate his dictatorship. With the upper and middle classes silent in satisfaction, there would not be any class in Philippine society capable enough to criticize and oppose him.

Suppressed press

One of the most important institutions of democracy in any society is the press, regardless of its flaws. It functions as an agenda-setter and watchdog especially against the excesses of a government with its tremendous powers. It's no wonder then that when martial law was declared in 1972, one of the first to get demolished was this institution.

The first Letter of Instruction signed by Marcos ordered the Press secretary and the defense secretary "to take over and control or cause the taking over and control of the mass media for the duration of the national emergency, or until otherwise ordered by the President or by his duly-designated representatives."

This did not mean that there were no media at that time; what was vanished was critical media.

All newspapers, magazines and television stations were closed down. Among the anti-Marcos media organizations that were closed were the old "Manila Times," "Daily Mirror," "Taliba," "Manila Chronicle," "Philippines Free Press" and "Graphic."

Leading media men such as Joaquin Roces, Eugenio Lopez Jr, Amando Doronilla, Max Soliven and Napoleon Rama were arrested and detained. Materials critical of the government were banned, and before anyone could print he should first secure the permission of the Department of Public Information (DPI).

This did not mean that there were no media at that time; what was vanished was critical media. Publications that were allowed to operate were those controlled by associates of Marcos. Among these were the "Philippines Daily Express" of Roberto Benedicto, "Times Journal" of Benjamin Romualdez, "Bulletin Today" of Hans Menzi and "Evening Post" of the Tuveras.

There was also strong censorship even among these "crony" newspapers. Censors would sit next to editors to weed out materials critical of the man, and woman, at the Palace. There were also military men and government lawyers who regularly visited the offices of these publications.

The "crony" papers and the muzzled media were one of the large pieces of the scheme of Marcos to sabotage Philippine democracy, and unfortunately he succeeded.

The "crony" papers "clearly did a great disservice to the nation by preventing a large body of Filipino citizens from being properly informed," Alice Colet Villadolid, a journalism professor and former New York Times correspondent, said in a Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility article. — Philstar.com NewsLab