I n one of his war stories, Ferdinand Marcos claimed that he had heroically defended the junction of Salian River and Abo-Abo River in Bataan for five days from January 22 to 26, 1942.

He only had a hundred fighting men in the suicidal action against 2,000 highly-trained and well-equipped Japanese troops.

His action has allegedly delayed the fall of Bataan... or so the story goes.

Military and diplomatic history expert Ricardo Jose, however, casted doubts on this story.

By sheer numbers, Jose argued that a hundred troops successfully blocking 2,000 is physically impossible. He added that Marcos was an assistant intelligence officer and not an infantry soldier who engages in combat.

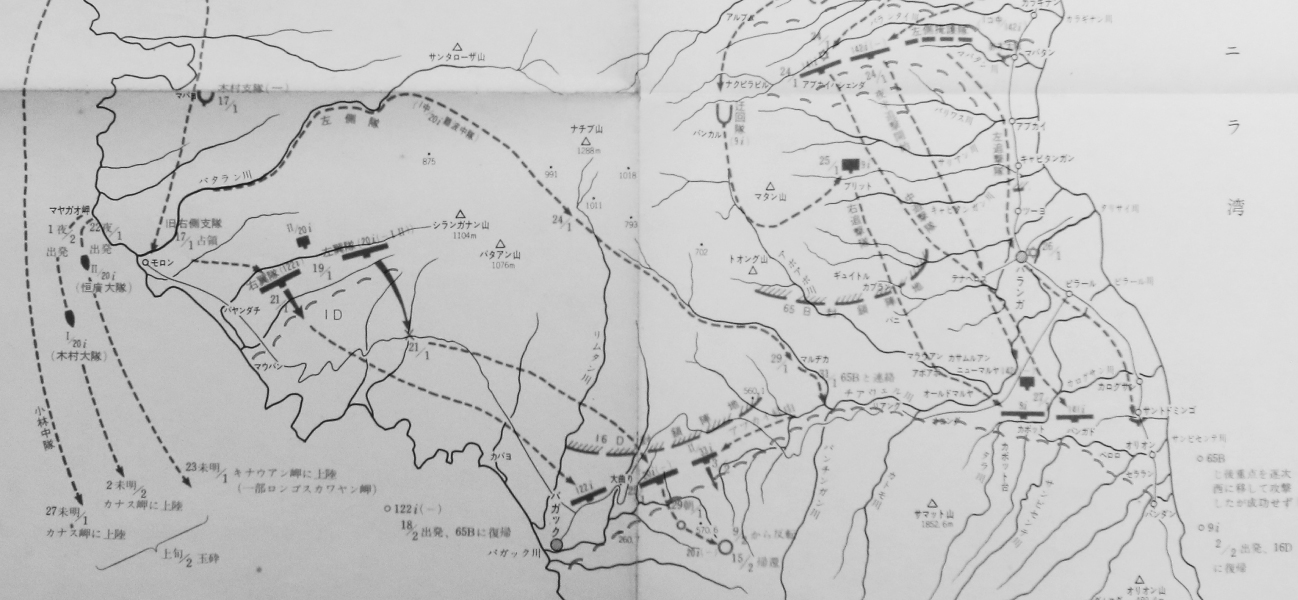

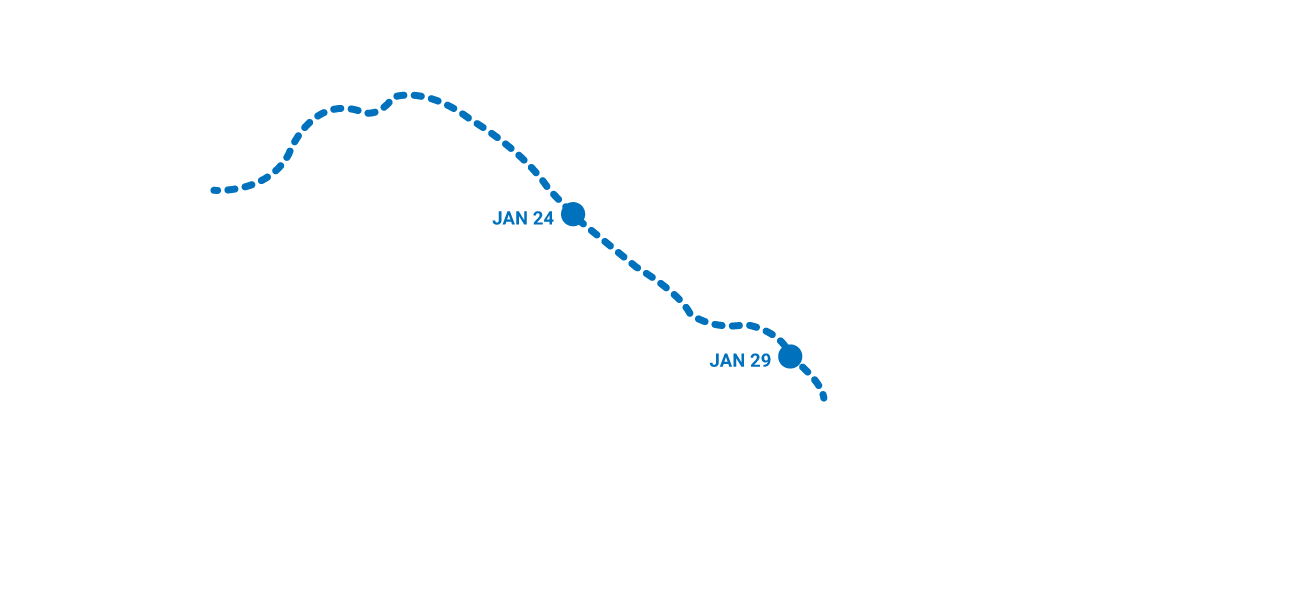

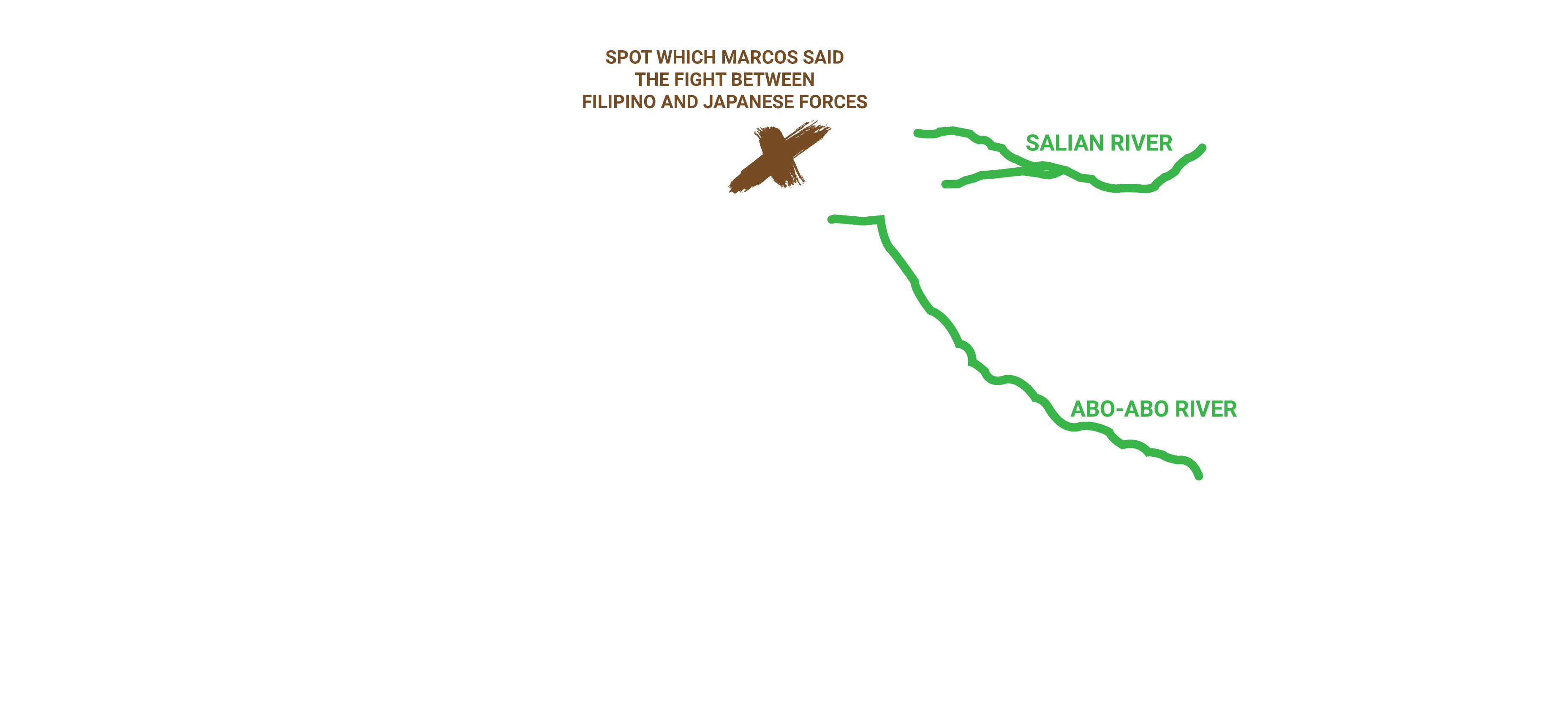

A map based on official records of the Japanese government, showed by Jose, revealed that no clashes occurred at the junction. The map also showed discrepancies in Marcos' accounts on the dates and the position of troops.

The blue line represents the Japanese troops while the red line represents Philippine and US forces. The map shows there were no clashes at the junction of Salian and Abo-Abo Rivers on the location and dates late President Ferdinand Marcos mentioned

Photo of the map highlighting Salian and Abo-Abo then the junction

Sixteen years after the supposed incident, Marcos—then a congressman—received a Medal of Valor for his claimed heroism. The citation was one of the arguments the Solicitor General presented to the Supreme Court in September 2016 to argue that Marcos deserves to be buried at the Heroes' Cemetery.

Battle of films and books

If you look at the world conditions at that time, karamihan ng world leaders at that time were war heroes... So parang ganun yung idea na in order to become a more effective political leader kailangan World War 2 hero ka din.

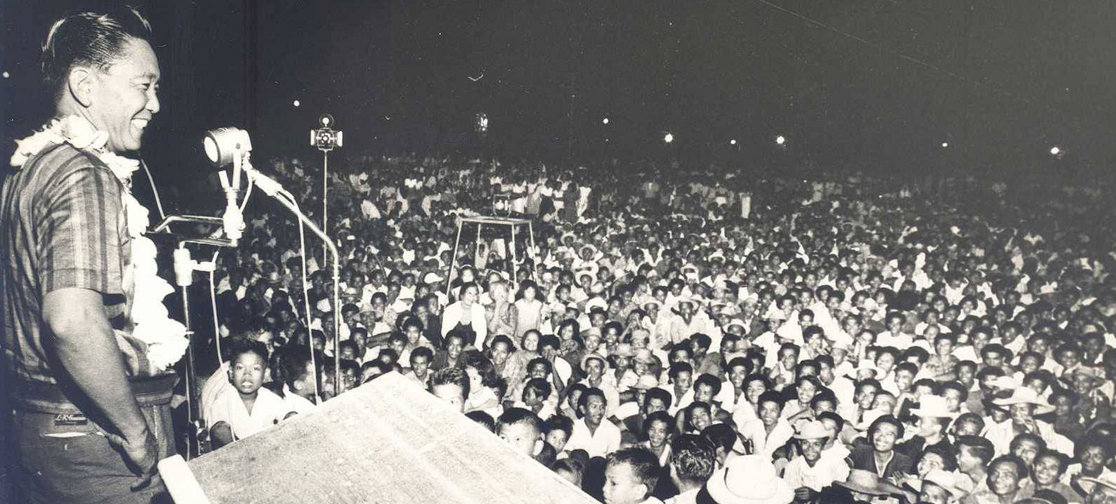

Marcos' supposed heroism was decisive in his rise to power. He won the presidency in 1965 against incumbent President Diosdado Macapagal and was reelected in 1969.

"If you look at the world conditions at that time, karamihan ng world leaders at that time were war heroes. Sa US Eisenhower, siya 'yung top US general sa Europe, 1960s si Kennedy was president of the US war hero din siya sa South Pacific, sa Europe si Charles de Gaulle, sa France war hero yun," Jose explained.

"So parang ganun yung idea na in order to become a more effective political leader kailangan World War 2 hero ka din."

The 1965 election was a battle of books and films. Marcos used his commissioned biography "For Every Tear a Victory" by American writer Hartzell Spence. Macapagal released "Macapagal the Incorruptible" written by Quentin Reynolds, an American, and Geoffrey Bocca, a British.

The biopic "Iginuhit ng Tadhana" depicted Marcos as a war hero. Meanwhile, "Daigdig ng Mga Api" portrayed Macapagal as a savior from poverty.In the 1969 presidential elections, then Sen. Sergio Osmeña accused Marcos of being the "most corrupt in Philippine history." Marcos retaliated by raising that Osmeña collaborated with the Japanese during the war by doing business with them.

The fabulist Mr. Marcos

Stories in "For Every Tear a Victory" became the basis of "what journalists wrote and American officials believed" about Marcos, New York Times veteran journalist Raymond Bonner wrote in his 1987 book "Waltzing with a Dictator: The Marcoses and the Making of American Policy."

Bonner noted that Marcos "could tell the most brazen lie with the straightest of faces, then continue telling it until it became accepted as fact."

Spence's biography was reissued in 1969 under the title "Marcos of the Philippines: A Biography."

Marcos "could tell the most brazen lie with the straightest of faces, then continue telling it until it became accepted as fact." – Raymond Bonner, author of "Waltzing with a Dictator"

Photo courtesy of the National Library of the Philippine

For years, his war tales were largely uncontested.

But in November 1982, World War 2 veteran Bonifacio Gillego wrote a series of articles which debunked the late dictator's feats.

The series published on WE Forum resulted in the jailing of the paper's publisher-editor, the late Jose Burgos, and fourteen of his staff for subversion and rebellion.

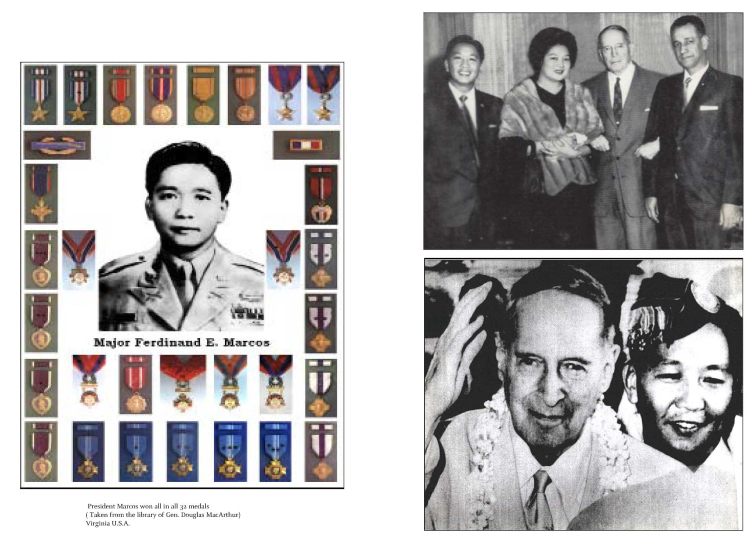

Gillego found that out of Marcos' 33 medals and awards, only two were given during World War 2. One was the Gold Cross and the other the Distinguished Service Star. Both were given in 1945 and both contested by Marcos' superiors.

The gold cross was awarded to Marcos, supposedly a colonel of the 14th Infantry of the United States Armed Forces in the Philippines-North Luzon then, for "gallantry in action at Kiangan, Mt. Province, in April 1945." Marcos allegedly spotted camouflaged enemy trucks a mile away and by himself ambushed them. The Japanese allegedly fled after a 30-minute firefight.

The Distinguished Service Star, meanwhile, was for his outstanding achievement as a leader of the 8,200-strong guerilla group Ang Manga Maharlika. The citation read:

"For outstanding achievement as a guerrilla leader. After escaping from the Fort Santiago Kempei Tai, Marcos supported ex-Mayor Vicente Umali, organizer and commanding general of the PQOG (President Quezon's Own Guerilla)... Despite his illness, he stayed at the headquarters in Banahaw to guide both the staff and combat echelons. He refused the rank of 'general' offered him by General Umali and organized his own guerrilla group known as the Maharlika."

Marcos' regimental commander, Col. Romulo Manriquez, in an interview with Gillego said the former was an S-5 who handles civil affairs and was never assigned to patrol or combat. Not to mention that geographically, it was impossible to spot Japanese trucks a mile away from the regimental command post as the nearest road was half a day's hike away.

It was also found that Marcos was not a colonel but a lower rank of captain. And he was never recommended for any decoration by his 14th Infantry adjutant, Capt. Vicente Rivera.

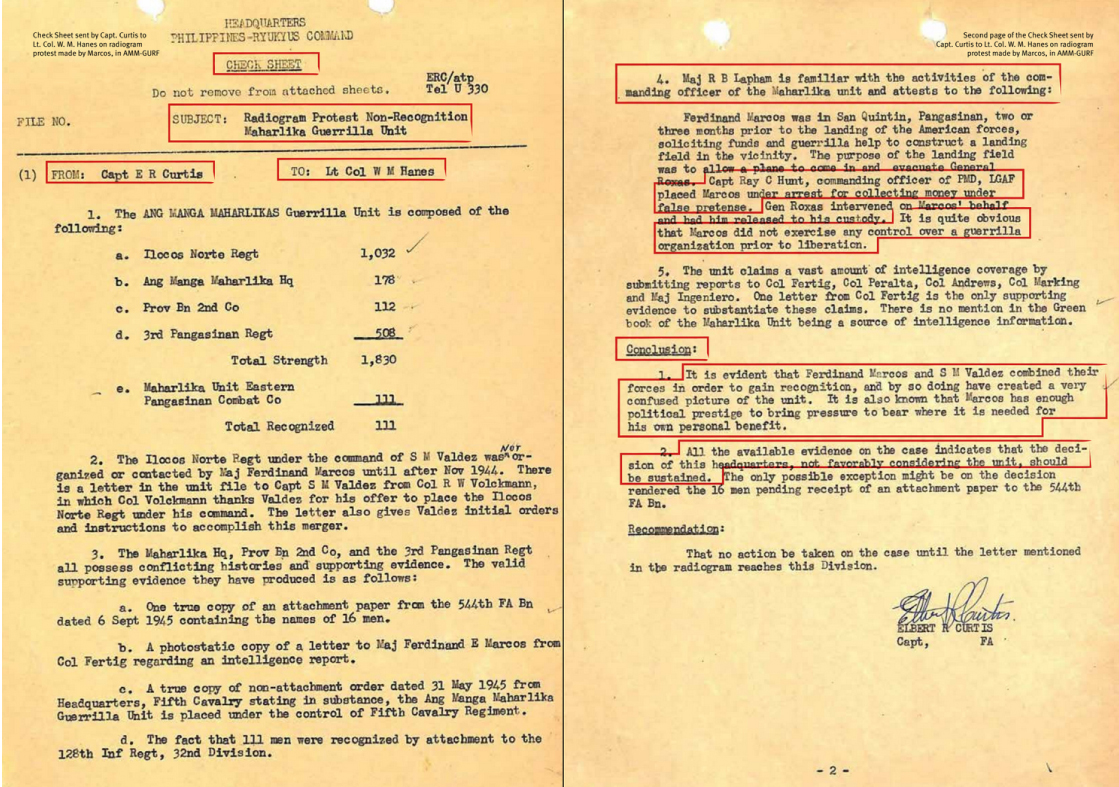

As for Ang Manga Maharlika, repeated investigation by the US Army found that the guerrilla group was, according to its judgment, nonexistent. The now-declassified File No. 60 detailed Marcos' quest for official recognition of the guerrilla group Ang Manga Maharlika, which he later changed into Ang Mga Maharlika. Recognition by the US Army as a guerilla meant getting back pay, and the longer the service the bigger the remuneration.

The US Army denied the recognition of the guerilla group on June 7, 1947 citing reasons such as:

- The lack of sufficient acceptable evidence to prove their record of service. Adequate records were not maintained and a definite organization was not established.

- The unit did not devote entire efforts in fighting Japanese forces in the field and did not contribute materially to the eventual defeat of the enemy. In fact, the probe found that "[m]any members apparently lived at home, supporting their families by means of farming or other civilian pursuits and assisted the guerrilla unit on a part-time basis only."

- Impossibility that its claimed strength and sphere of operations were true given terrain problems, limitation of communication facilities and the degree of Japanese anti-resistance activities.

Marcos protested the decision in an angry cablegram. Capt. Elbert Curtis responded with a strongly worded rebuttal. His conclusion was:

- Ang Mga Maharlica Unit under the alleged command of Ferdinand Marcos is fraudulent.

- The insertion of his name on a roster other than the USAFIP, NL roster was a malicious act.

In an earlier response, Curtis also wrote: "It is also known that Marcos has enough political prestige to bring pressure to bear where it is needed for his own personal benefit."

He cited an account attested to by American guerilla leader Robert Lapham detailing how Marcos was placed under arrest by former Army captain Ray Hunt Jr. for collecting money under false pretense. Gen. Manuel Roxas intervened on his behalf and had him released.

Ferdinand Marcos was in San Quintin, Pangasinan, two or three months prior to the landing of the American forces, soliciting funds and guerilla help to construct a landing field in the vicinity. The purpose of the landing field was to allow a plane to come in and evacuate General Roxas. Capt. Ray C. Hunt, commanding officer of PMD, LGAF placed Marcos under arrest for collecting money under false pretense. Gen. Roxas intervened on Marcos' behalf and had him released to his custody.

The final and irrevocable refusal on the claim was issued on March 31, 1948.

The claims of 111 men listed on the Maharlika roster, however, was recognized for their "aid during the liberation of the Philippines." But a Jan. 23, 1986 article of The New York Times said there were conflicting statements in the Army records on "whether the United States intended to recognize the 111 men as individuals or as a Maharlika unit attached to American forces after the invasion."

The same article also cited a Philippine Army document stating that several men listed as Maharlika members sold and purchased steel cable—an important wartime commodity—to enemy forces.

Lapham in a May 31, 1945 communication said that 24 men led by Marcos who identified themselves as Maharlika were "employed by [his] organization to guard the Regimental Supply Dump and perform warehousing details." He, however, did not recommend them for recognition "because of the limited military value of their duties."

It is also known that Marcos has enough political prestige to bring pressure to bear where it is needed for his own personal benefit.

Hunt, who during the war directed guerilla activities in Pangasinan, where a Maharlika unit purportedly operated, was quoted by New York Times countering Marcos's claims. He said Marcos never led a large guerrilla organization.

"Nothing like that could have happened without my knowledge."

Although the Army documents did not successfully refute Marcos' claim to leadership of a parent organization known as Maharlika—under which a special intelligence unit officially recognized by the US military operated—the story behind the guerilla group is clouded by doubts and counterclaims, Time correspondent Sandra Burton said in her 1989 book "Impossible Dream: The Marcoses, the Aquinos, and the Unfinished Revolution."

She noted that an affidavit by Narciso Ramos, father of former President Fidel Ramos, offered an explanation on why Marcos failed to get accreditation for the parent organization. The explanation offered a different perspective on Marcos' imprisonment from Lapham's.

The senior Ramos was wartime chief of the special intelligence section of Maharlika. According to his account, Marcos had failed to meet the American filing deadline for a roster of members of the parent organization, because he was thrown in the brig by an American captain acting on information fed to him by "unsympathetic" rival guerrilla groups. Lacking that central roster, US military authorities granted sole accreditation to the Maharlika intelligence branch, on the basis of a more limited membership roster submitted by Ramos, who was acting as commanding officer in Marcos' absence.

Burton said exaggeration and fabrication were so commonplace that over one million Filipinos claimed guerilla status after the war even though the US estimated that only 250,000 actually fought the Japanese.

Stolen valor

It was also questioned why virtually all of Marcos' medals were awarded long after the war.

Eleven medals were given in 1963, when Marcos was Senate President, according to Gillego. Of these, 10 were awarded on the same day on December 20.

He added that eight of Marcos' "American and Philippine medals" were campaign ribbons given to all who participated in the defense of Bataan and the resistance against Japanese. One of the awards was received by Marcos on Sept. 17, 1972, his 55th birthday.

He also noted that some medal citations were for the same event.

Marcos presented affidavits in 1962 from already dead witnesses attesting to his war exploits, Primitivo Mijares wrote in his 1975 book "The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos" citing official statements in preserved journals of the Congress.

The medals were awarded the same year by the newly installed Liberal Party administration. Then Secretary of Defense Macario Peralta Jr. said he approved the requests for medals in exchange for Marcos' pledge that he would not run against Macapagal in 1965.

Mijares, who served as Marcos' chief propagandist, would later disappear never to be found again after the publication of his tell-all book on the excesses of the first couple and their cronies.

The credit was taken from him. Kaya mayroong tampo ang pamilya as far as the Marcoses are concerned... They basked in the glory of someone else's credit.

Gillego also debunked Marcos' claim of being the hero of Bessang Pass, the battle that led to the surrender of General Tomoyuki Yamashita.

A passage from "Marcos of the Philippines" narrated how he single-handedly defeated 50 enemy soldiers in defending Bessang Pass. It read:

"On April 5 [1945] Ferdinand won his second Silver Star. He was at a command post .... in Kiangan .... still defending Bessang Pass.... What he discovered was a well-camouflaged infiltration by fifty Japanese....

Sending his man back to alarm headquarters, Marcos stood alone between the attack force and its goal, a Thompson sub-machine gun under his arm. But now the element of surprise was with him.... the enemy... did not see Ferdinand at all. At a point-blank fifty yards, he began to shoot, killing the commanding officer with the first burst. Disorganized, the detachment regrouped and attacked, but Marcos repulsed it. For half an hour the skirmish continued, with grenades and automatic-rifle fire.... Still unsupported, Major Marcos counterattacked. He had pursued the Japanese nearly two kilometers down the trail before reinforcements reached him."

Gillego said that the late dictator was never mentioned as a participant in many first-hand accounts of the battle that lasted between January 9 and June 15 in 1945.

Manuel Rigor, the son of Colonel Conrado Rigor Sr., one of the heroes of Bessang Pass, also discounted Marcos' participation in the historic battle, in an interview with ABS-CBN News.

Conrado, then a major and commander of the 3rd Battalion of the 121st Infantry, was handed Yamashita's Rising Sun flag after the surrender.

"The credit was taken from him. Kaya mayroong tampo ang pamilya as far as the Marcoses are concerned... They basked in the glory of someone else's credit," Manuel said.

He said there was no proof that Marcos was even at Bessang Pass in Ilocos Sur, based on accounts from his father and those who fought with him.

In a study released by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) on Independence Day last year, it said that Marcos lied about receiving three of his US medals: the Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star and Order of the Purple Heart.

Marcos' fabricated heroism was one of the reasons the state agency on the preservation of Philippine history disputed his burial at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

A doubtful record, it argued, does not serve as a sound basis of historical recognition, let alone burial in a space for heroes.

"The rule in history is that when a claim is disproven—such as Mr. Marcos's claims about his medals, rank, and guerrilla unit—it is simply dismissed," NHCP said. — Philstar.com NewsLab